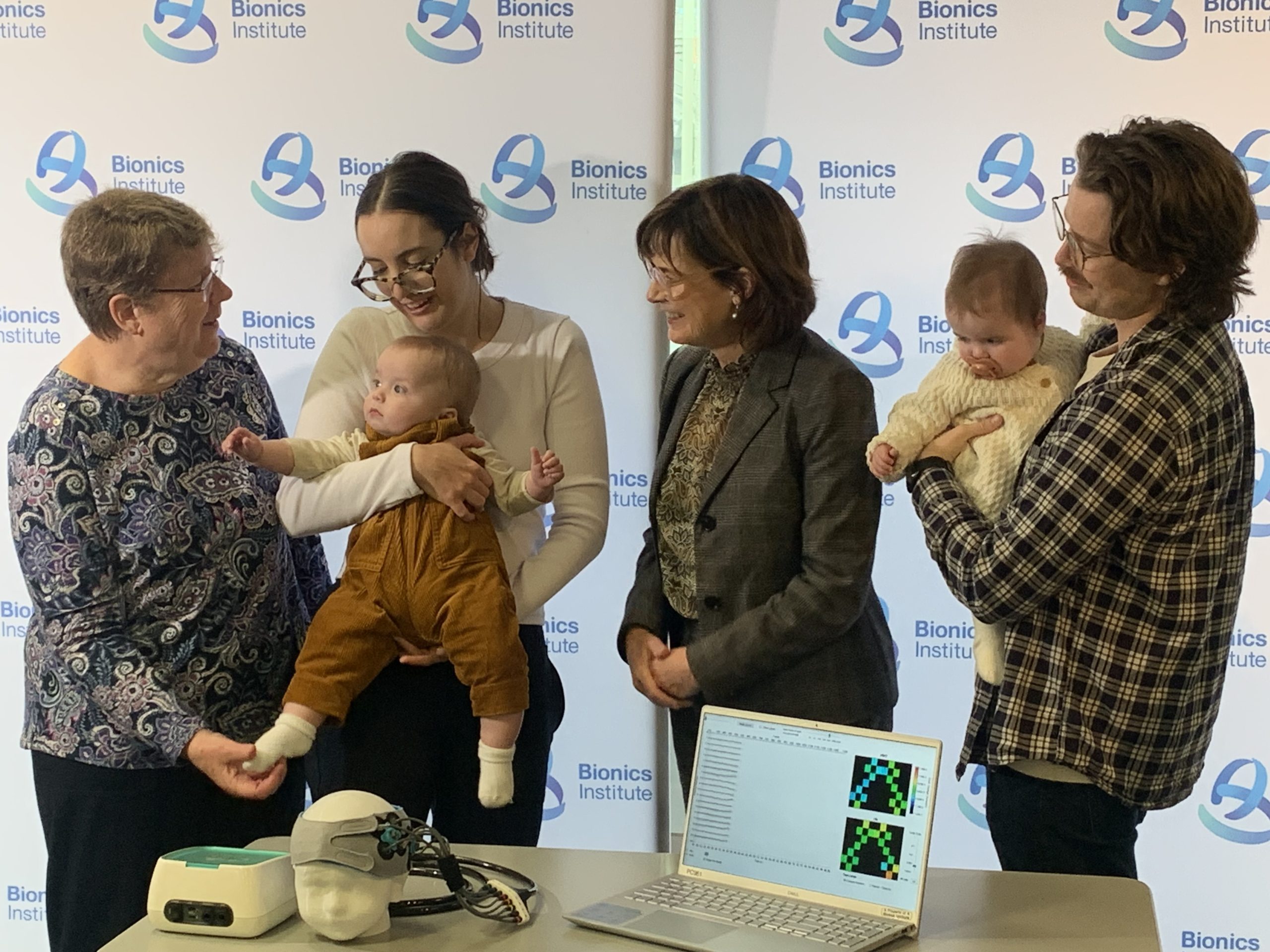

Ever since their son Isaac was born in August 2019, Michelle and Simon have been on the hunt for answers.

First there was his heart, which had three distinct holes in it, as well as an alarming respiratory rate of 120 bpm. Then there were two failed hearing tests, followed by a diagnosis of auditory neuropathy in his right ear. And just before they left hospital, at four weeks of age, he was diagnosed with coloboma, a rare condition resulting in a missing piece of tissue in the retinas of his eyes.

Eight months on, Isaac is making great progress. Two of the holes in his heart have healed over, and he’s turning into a bouncy and expressive baby. Two months ago, his relieved parents were told that he could see through both eyes. But his hearing, at least in his right ear, remains a mystery.

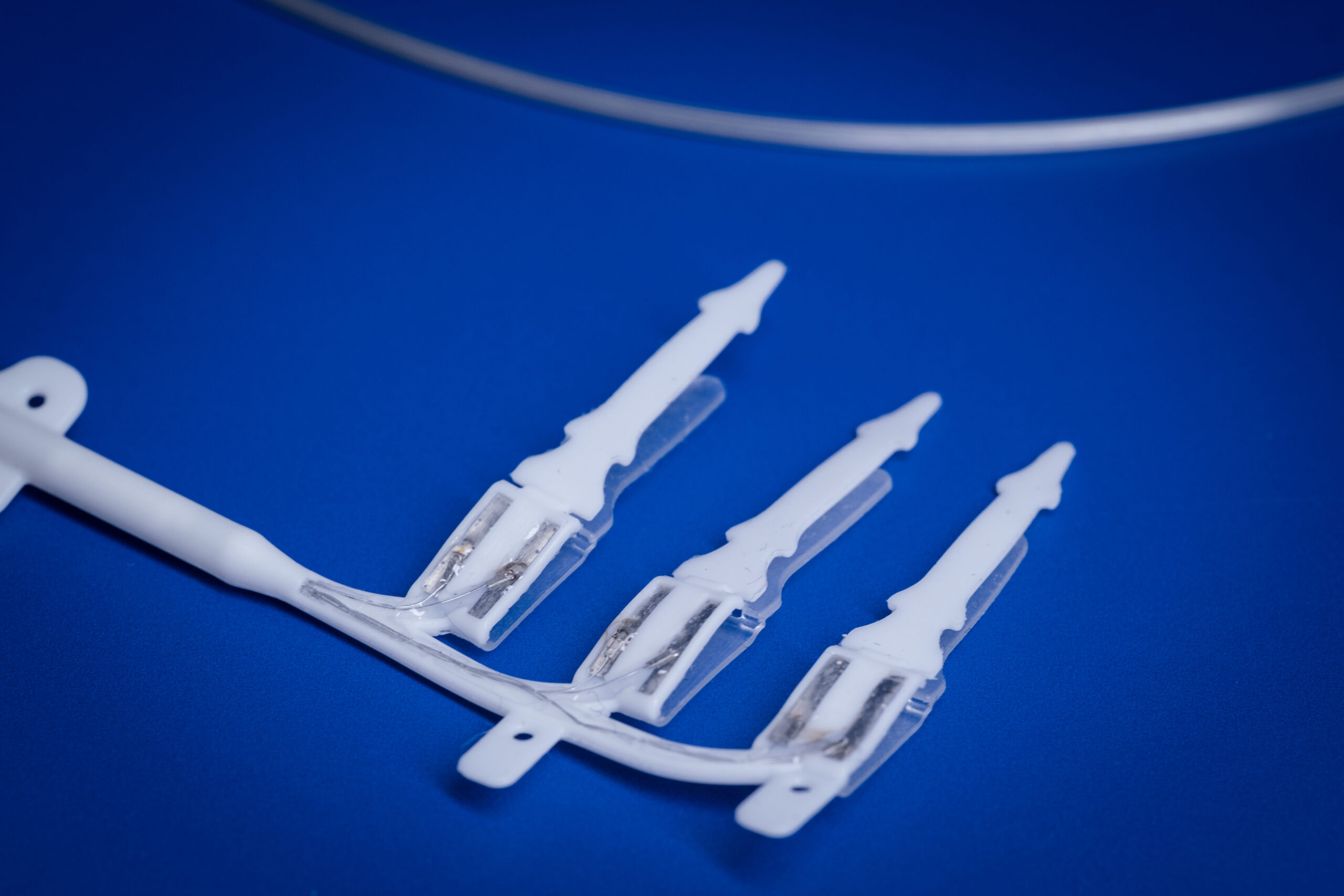

“His audiologist thinks he can hear loud noises of 80 decibels, the equivalent of a lawn mower, in his right ear,” says Michelle. “But if she sets a hearing aid at that level and she’s wrong, it could damage his hearing. We’d love to get him a cochlear implant, which have proved so successful with auditory neuropathy – but we’re in limbo until the doctors can give us a definitive answer.”

The Beards are used to hearing tests, having undergone four diagnostic assessments and an MRI of his inner ear and auditory nerve, which showed up no anomalies. But the enduring mystery of auditory neuropathy – where sound information is disrupted between the inner ear and brain, often for no apparent reason – means doctors may not know exactly what Isaac can hear until he can tell them.

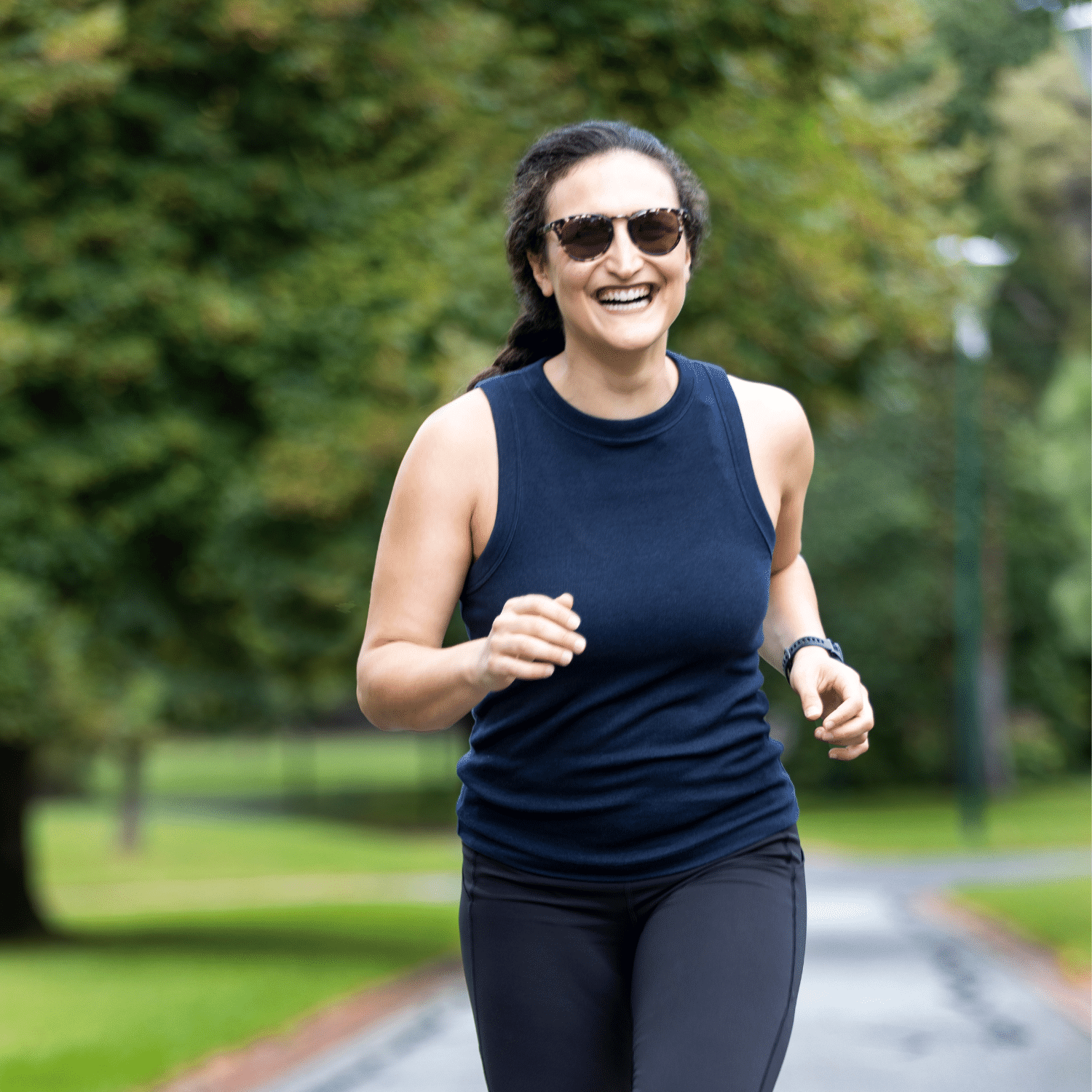

“Actually, I think we’re pretty lucky,” says Michelle, a 38-year old kindergarten teacher. “Isaac is a happy baby and he has good hearing in his other ear, thank God. If he had auditory neuropathy in both ears, we’d have absolutely no idea what he could hear and that would be horrific.

“But if there was a technology that could tell us what he’s actually hearing in his brain, it could have saved us so much heartbreak in terms of knowing what’s going on, and being able to plan and move forwards to support him in the best way.”

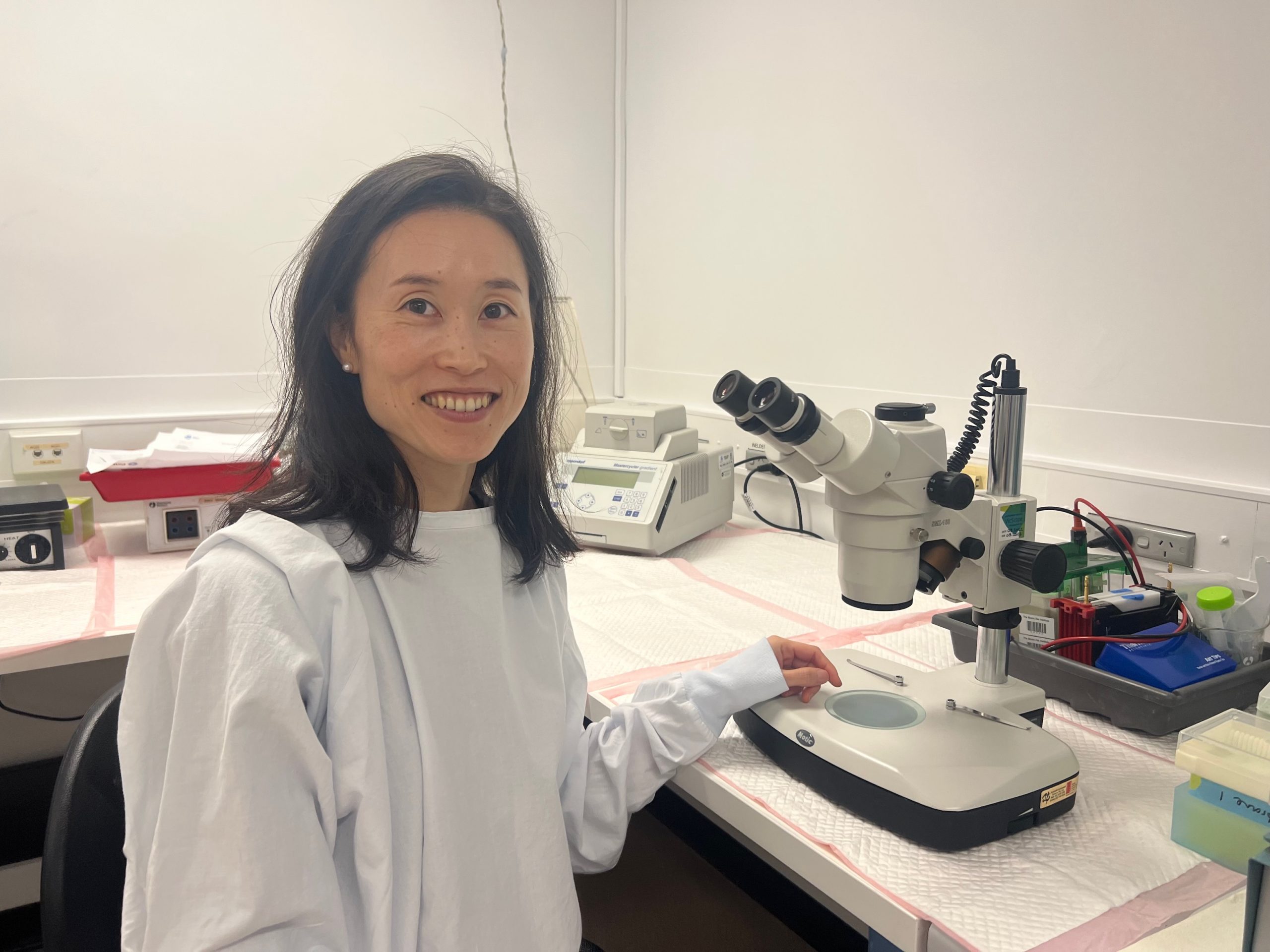

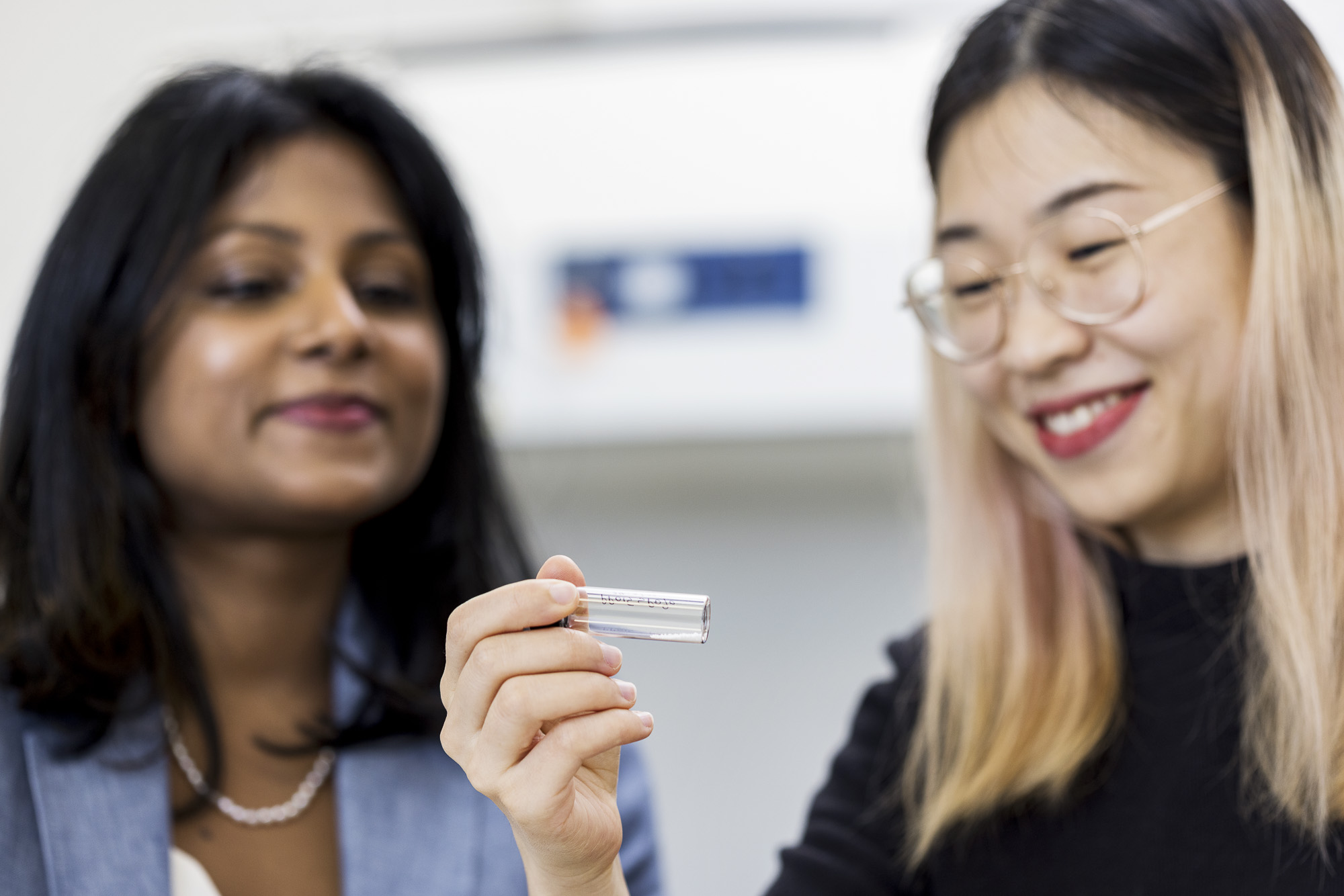

At the Bionics Institute, Professor Colette McKay is leading the development of an innovative clinical system called EarGenie™ which uses functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) to image brain activity. At diagnosis, EarGenie™ can provide an accurate and detailed hearing assessment so that appropriate hearing devices can be confidently selected and programmed. Technology such as this could help children like Isaac and over time, this system can be used to evaluate and fine tune devices to optimise each child’s hearing and monitor their language development.

Michelle has studied the science, and knows how crucial the first two years are for a baby’s language development and the social interaction and confidence that come with it.

This is the time when a baby is really learning, even in these first 12 months. If we could know to what extent Isaac can hear, we could get an implant or a hearing aid to enable him to have surround sound, and find the right therapies and techniques to start building his communication skills. We’d be six months ahead of where we are right now. Michelle, Isaac’s mother