Med Tech Talks

From clinician to entrepreneur with Dr Devinder Chauhan

Macuject is a digital health company that harnesses AI to provide imaging and data solutions for ophthalmologists to them make clinical decisions when treating age-related macular degeneration.

Dr Chauhan founded Macuject in 2017 and is currently making the transition from clinician to entrepreneur as he and his team aim to roll this product out in eye clinics both domestically and internationally to improve visual outcomes for patients worldwide.

In this episode you will hear about:

More information:

Learn more about Dr Devinder Chauhan

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:01:30] Thanks very much, Robert.

Robert Klupacs [00:01:32] If we can start, take you right back. I learned a little bit about you for our listeners. You completed your Bachelor of Medicine and Surgery and your M.D. in the United Kingdom at the University of London. I’d like to know where it all began for you and why did you choose to become a doctor? Firstly. Why did you decide to become an eye specialist? And ultimately, we’d like to know how you found your way from the UK to Australia.

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:01:55] Yeah. So actually, since before I was born, my mum wants me to be a doctor. I’m an Indian son. That’s what is they all want. And at the age of 12, I told her to stop bothering me. And she did. And then what happened was later on when it came to thinking about what university degree to do, I was one of those people who ended up taking medicine because I could not necessarily because I should. I was interested in basically physiology, how things worked in the body, and that was pretty much it at the time. And so what’s happened since then, over time is that I’ve been able to appreciate the science and then the people side of things and have grown into medicine. So I’m not one of those people who, from the age of four, always wanted to help people in medicine. But what’s really cool is that I actually have been able to do that and that that’s just happened over time. There was a point at which I was frustrated by the lack of science in normal medicine when I was when I was being trained. So I went sideways and did a research M.D. thesis, which was all about science and how those CT scanners work. That’s the imaging devices we used to look at macula’s, though I look at it everyday now, and after that I just went into clinical medicine. One of the things I did during my training in ophthalmology, which and I explained the reasons for that in the second was actually came to Australia in 2001, just down the road at the Eye and Ear Hospital, as a fellow, as a retinal fellow and working, that was fantastic. But living in Melbourne was even better and for me it was really about the lifestyle of living in Melbourne compared with England, and so much so that I remember. Wednesday, July the fourth, 2001 10 p.m. I was playing tennis at Grace Park and I thought, Hang on, this is the middle of winter and I’m playing tennis with other people at night. This is an amazing place to be. So that was one of the reasons.

Robert Klupacs [00:04:07] Oh fantastic. So what led you from that early training to become an ophthalmology in particular? What was the reason to specialise in the eye?

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:04:14] That was basically because I really liked the medicine part of being a doctor because he thought a lot and it was problem solving. But at the same time I really, really enjoyed the surgery part because he actually did something. It wasn’t just in your head, you actually did something with your hands. And ophthalmology really is probably still the best combination of those two. And that’s what I like. It was it was being able to think, see problems. And in fact, even the whole eye being a window to a soul bit where you can see other things in the eye that are relevant to the rest of the body. Just having that whole thinking and doing rather than just one of those.

Robert Klupacs [00:04:55] So your company, as we said at the beginning, is a digital based technology which hopefully will take us through in a moment to help doctors treating wet AMD or age related macular degeneration. Yeah, just for our listeners I’m not sure many people really understand this different types of macular degeneration. These are the parts of diseases that get treated. Could you give us a little bit of the background to what it is? Yeah, and what the issues are for the patient.

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:05:22] Yeah. So your eyes like a camera with the lens at the front that’s inside and the film at the back. And the film is called the retina and that is part of the film. The retina sees different parts of what’s around you, but the most important part is the central part, and that’s called the macula. The macula is therefore responsible for seeing, for driving, reading, watching TV, and really importantly recognising faces. And pretty much everything you think of when you think about seeing. So with age related macular degeneration, as time goes by, there’s a process of, for want of a better term, junk material that collects behind the macula that shouldn’t be there, that slowly accumulates. And then after a while, and that’s still called dry macular degeneration. And after a while, if it becomes advanced, it can go into one branch, another branch, or actually both. The branch that’s less common is called wet macular degeneration. And that’s where you get these abnormal blood vessels growing behind the eye, behind the macula that ooze and leak and bleed, and that causes scarring and pretty quick loss of vision within a few weeks to months. The other type of advance is calleded dry or geographic atrophy, and that’s where little patches of the macular just disappear and they slowly very slow burn progress towards the centre and then take away the central vision. To date in Australia, we can only treat the wet macular degeneration that’s with injections in the eye regularly, frequently and for the rest of people’s lives. The other types of geographic atrophy in the States is now treatable. There are actually two drugs that came out this year, but they’re not yet available in Australia.

Robert Klupacs [00:07:12] But that’s been really helpful and a little bit of a background understanding is a few years ago and when we aimed for many years is very difficult to treat. A lot of people became blind. There’s a revolution, I think was in the like early 2000s when the Anti-VEGF’s first became available and seen to revolutionised eye care. And the first clinical trials were quite spectacular. Those drugs are now very widely used and I think in Australia I think there’s two major drugs in the middle, one and the five on the PBS, enormous cost of the system because they save people from blindness. But what I’m hearing from a lot of ophthalmologists is what they hope to be seeing with them isn’t quite what they’re seeing in the real world. Can you comment on that from what you’ve seen? So I know this leads into what you’ve developed, but just put that in perspective. I think a lot of people think, well, this is an absolute gold mine. I’ve been diagnosed with it, but I’ll go and get my doctor to fix it and I’ll be fine. But what do you see in practice with Anti-VEGF’s?

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:08:10] So the first thing used to be that people were referred to late for wet macular degeneration, but that’s not the case now. Optometrists are excellent at picking that up very early, so that’s not an issue. But what then happens is you start treating people and these people are normal people on the street. They’re not people who were specifically selected for a clinical trial. So when clinical trials are done, they’re basically bring people in and recruit people who are most likely to get the greatest benefit from the treatment. So clinical trials don’t actually answer what would happen in the real world in the first instance. So we should never be too surprised that we’re not getting as good results in the real world as clinical trials. Having said that, though, it is possible to get very good results and we will see them. The difficulty is, though, that people and this is different is a fixed protocol or a very commonly used protocol for deciding how to give treatments and when and which drug to use, etc. But that’s not always applied rigorously for a whole bunch of reasons. And then even when doctors do recommend certain times, the patient should come back for an injection. They don’t always come back either because they’re sick. They don’t appreciate the importance of the treatment, don’t really understand the relevance. There’s this concept of injection fatigue. I’ve had so many injections, why do I need to keep coming back? And there’s a need for constant education and encouragement. And if you don’t get enough injections over time, vision drifts off and you end up losing more. But there’s also the expectation. So the when I talk to patients, I say to them the number one reason for doing these injections is to stop you losing more vision. And the number two reasons to gain vision, because the number one reason, if your vision doesn’t get better, that’s actually a success. Because if we stopped or didn’t do the treatment, it would get far worse. So there’s a whole bunch of factors affecting how often people have them and whether they get enough injections.

Robert Klupacs [00:10:20] When I understand that scene, any practice and you thought, gee, there’s got to be a better way to improve that for both of the patient compliance, getting them back and for the doctor to make the right decision. So that led to the development. What I understand is your whole technology, your digital technology. Can you explain for our listeners what that actually is and the benefits it gets for the doctor but also for the patient?

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:10:45] So the first thing that actually drove the need to do something was a growing number of patients seeking treatment. So I was treating a lot of patients and needs a workflow tool to make it easier. And the biggest pain at the time of treatment was making decisions. To make a decision, you have to look at one piece of software to look at scans of the macular and then look another piece of software to look at the electronic medical record to see what the patient’s in for, what’s happened to them in the past. And then in order to make the best decisions, you need to see what’s happened from the past. How did they how were they doing with a previous drug at a previous interval between injections? And then look at find the scans that corresponded to that, compare them and make a decision essentially to say, okay, so you’re on the correct drug, but we can try this interval or whatever. That takes time. And it it’s confusing and we don’t have time. We don’t have time to treat these all these patients. So what the software is, is essentially bringing that all onto a single screen. So the images, the scans get uploaded to the cloud. There’s machine learning in the cloud that finds the abnormalities. We’re treating this fluid collecting in the macula from months and then measures it. And that feeds into a decision tree. A decision tree. That’s the gold standard decision tree for doing injections. But very importantly, the decision tree is configured by the doctor to their own preferences so that they actually it’s a bit like Google Maps for injections. So they actually get to choose which drug to start with and how they use these drugs and when they consider switching. So that the results of this is that when the doctor uses the software, they literally everything they need on the screen to make a decision, a few clicks for each eye will lead them to their own decision being delivered to them, their own recommendation faster and more consistently than would otherwise happen. So really interestingly, that’s what I thought it was going to be a workflow tool only to start with. But then it became apparent that seeing your own recommendations yourself means you’re more likely to do it, which means that it’s a nudge tool. It’s part of nudge theory. So doctors ended up doing slightly more injections, compensating for the undertreatment that may have been happening before and that resulted in better outcomes. I was doing myself many more injections on average per patient, pretty much in that zone that’s thought of as being the optimal zone of injections. But my patients see statistically significantly better when I use Macjuect compared to when I was when I wasn’t using it.

Robert Klupacs [00:13:24] Wow, that’s amazing. You make it sound so simple. Oh, well, I had this problem. I put it together. I got a decision support tool. What I’m fascinated to hear is how that happens. And it’s like having a very busy retinal ophthalmologist. And you’ve created this incredible digital tool with machine learning in the cloud, and it’s got scale. There’s a journey there that you’ve got to tell us about.

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:13:44] Yeah. So it started off with me thinking, This is really easy. My job’s easy. You know, the classic sort of self-deprecating. It’s not that hard. How hard can it be? Sort of situation. And then I thought, we’ll just put this decision making into code. So it’s. It’s obviously just an if then situation. So we’ll do that. But then it became obvious that when we tested it, in fact, we’ve test. I’ve got a very busy practice of I’m responsible for roughly 8% of Victoria’s eye injections. So what that meant was I had the opportunity over and it took 18 to 24 months to test our protocols, to test our decision, trace to see if it would work. And what I discovered was that much of what my decision making was, was what people might call edge cases. But the edge cases were probably 25 to 30% of patients I saw. There was always a reason something was slightly different. The patient would come in early, come in late, the otherwise become affected, etc. So putting that into code was very difficult over time and we’ve then had to rewrite it so that it’s in a modular way that makes it much, much more usable later on. But the main learning was that we are used and I spent a lot of my own money on getting external consultants to do the work to build these different parts. And then it became apparent that actually we need to have internal capability into it ourselves because that way you’ve got more control and more understanding and then that’s actually a more robust way to move forwards.

Robert Klupacs [00:15:26] How did you fund the company? So you mentioned that most of it was your own money, but then you had to bring other people in, You had to build your own in-house capability. Have you continued to fund that yourself or have you brought investors into manage it now?

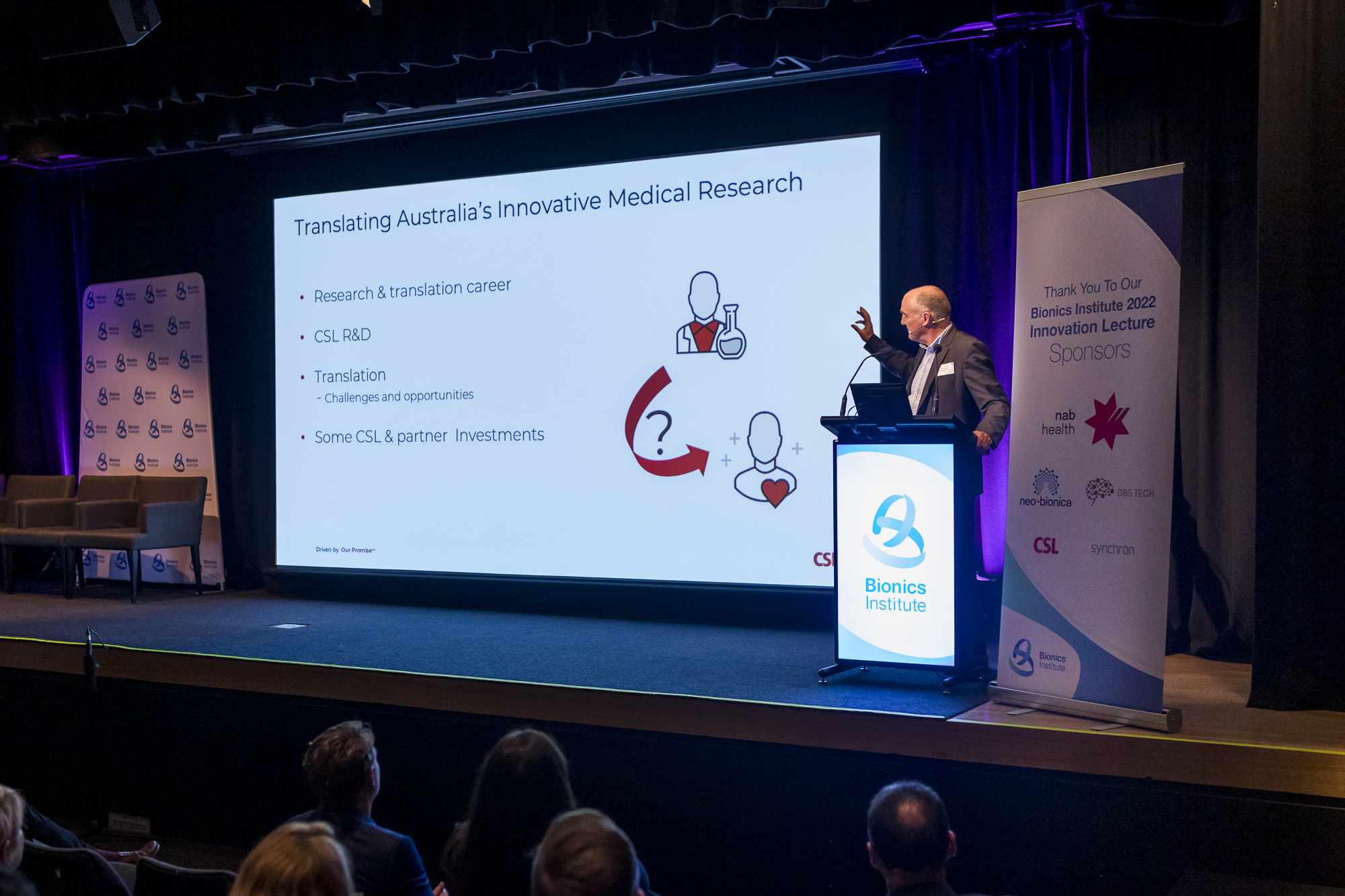

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:15:39] So initially, I was funding myself. I’m going to give a shout out to two national institutions or entities. The first is the R&D tax incentive. That’s where the government will give you a rebate. I think it’s 43 and a half percent of all the money spent on research and development. Without that, Macuject would not exist. I would still be just doing my normal day job all day, every day, and the product wouldn’t be there. And the second is the MRF. That’s the Medical Research Futures Fund, and that’s a fund that the government sets up. While I’m not sure which government, but it doesn’t matter. And what they do is they, they basically have grant programs and accelerators and commercialisation, things that actually help commercialise. So we got the first of those two grants that we’ve got through the MRF in the end of 2019. And then the second that’s that was a biometric horizon’s grant. And the second one we got recently is through AND Health, which is the Australia’s National Digital Health Organisation. Those have contributed hugely to not just money but actually the with biometric horizons, very much the rigour and the accountability. That means that you go on and do the right thing and actually do what you say you’re going to do. And with and health very. That’s a program we’re in right now and health plus program very much about not just encouragement but very importantly guidance and an opportunity to discuss and learn and develop and get input from local and international advisors money wise. We’ve also got to well, now three Australian retina specialists who invested the Australian Medical Angels, which is a syndicate of doctors, have invested, and we’re talking with some retina specialists in the US about investing as well.

Robert Klupacs [00:17:42] It’s fantastic. So what’s the plan? So at the moment you start in Australia and clearly quite successful in getting the uplift with your clinic and others. How big is the company today and what’s the plans for the future in terms of bringing this to the rest of the world?

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:17:58] So we have 12 people in the company and a process of recruiting an extra machine learning person and some people to work on the software, the front-end software, but also a commercialisation person for the United States. So, we’ve developed a lot here, but for it to be commercial, for make it to grow and be commercially viable long term and therefore be able to deliver back here in Australia, it needs to it’s one of those, if you can make it there, you can make it anywhere situation. So, we’re going to the US primary commercial markets.

Robert Klupacs [00:18:35] And what’s your model? Do you sell a service subscription, access to the doctor’s clinic and for a fee from your company and they, they pay it per time. They use it as just a standard one-off fee.

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:18:46] So importantly, the business model just keeps changing as time goes by. And the business model now is going to be something we have to test and that’s going to be both for wet macular degeneration and geographic atrophy, into which we’ve now expanded and pivoted at the beginning of this year. So, the business models vary depending on which of those bits of software are used, and we’re still working through the order of that. But essentially, it’s going to be assess the software as a service business to business subscription, the idea being that large optometry groups and large retina groups in the US and possibly even pharma companies will subscribe to our offerings and our offerings are now in geographic atrophy, spreading not just within the retina clinic, but into optometry and patient support as well.

Robert Klupacs [00:19:41] And it’s interesting you mentioned Pharma, because I was thinking as you’re speaking, whether there was positive or negative for pharma, because the positive for them is more injections get done because it’s better outcomes for the patients by doing this, possibly the otherwise it perhaps there’s less injection sound because the software is telling the doctor actually patients are different. So, what is what it’s been. New reaction from the pharmaceutical companies who sell these products about this decision support tool. Do they want it? Do they think it’s competitive or do they think it’s going to be helpful?

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:20:09] Pharma companies are really interested, partly because of the data analytics that can come out of it. This is where we can understand why doctors make the decisions they do, and that’s part of it. But I’m going to take it back a bit. I’m of a I’m of a social sort of level of group. It’s the sort of person who’s always been very, very cynical about pharma companies and very cynical about the reasons for doing everything and always thought it’s all about money and yes, it is all about money, but they actually do want to see people do well. Okay, So I have not met anyone in the pharma company who is not driven significantly by wanting patients to do well. So, I think the important thing is that they see that aligning with money because if patients are doing well, patients stay on treatment and patient and the governments will then subsequently be happy to pay for the next treatment, then the next one, the next one. So, I think there is alignment that, however cynical we might be, actually does work.

Robert Klupacs [00:21:18] Look back. It’s only six years, but you started becoming 2017. Quick question for you now. You know that you’ve gotten a retinal position to effectively being an entrepreneur. If you look back six years, do you think, gee, what have I done?

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:21:33] Oh, absolutely not. Absolutely not. I am. On a very personal level. This is a fantastic time. That Biometric Horizon’s grant kicked in early 2020. COVID time made me realise that I needed more time because I had more time on my hands because I couldn’t see as many patients and realise I need more time and just got into doing this. I find the problem-solving component, the everything’s new component, and very importantly, the switch from being the expert in everything in my clinic to knowing that I’m the expert. Nothing right now fantastic because it’s just so good to be able to be in a position where basically I’m constantly learning. Learning doesn’t happen that much in a private clinic in ophthalmology in any way really doesn’t happen that much.

Robert Klupacs [00:22:31] He guided you so you had this great idea. You could see an opportunity that needed to happen. And as you said, I knew nothing about what I needed to do, and I’m learning. But who did you reach out to? Who guided you early on?

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:22:42] Well, that was my first. Everyone makes mistakes. My first mistake was I just thought, I’m so clever. I’m the I’m a retina specialist. I know everything I need to know. I’m just going to build this and people will want it. That was the first ad, so I didn’t ask at that time. So I basically started developing this without asking for advice or inputs. And I know now that had I done so, I would have say time and definitely money and effort in doing that. So to be honest, the times at which I started getting more internal advice was in the last in the last four years because it was like obvious that this whole thing was much more difficult than I thought it was. I thought, as I said, I thought we were going to build this piece of software. It was going to be so obvious that it was so useful that people would just want it and then pay for it. That was incredibly naive.

Robert Klupacs [00:23:39] Good to me.

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:23:39] Yeah, but it was incredibly naive.

Robert Klupacs [00:23:42] So you’re going to go through that journey now. You’ve convinced, obviously, the Australian market, I suspect. But now you’ve got to convince the rest of the world if you’re getting the feedback from people in the United States to similar what you got in Australia, or they are asking you different questions, do they want you to modify it?

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:23:56] So in the U.S., I talked to people about the wet macular degeneration program before and they didn’t necessarily see how it would seriously add to that whole sort of environment and add to the improve their working so much. They could see how it might, but they saw barriers in terms of, “Yeah, but what about this? What about that?” So it was somewhat lukewarm even though they could all say that once it’s in, they’ll gain huge benefits from using the software. They could see that, but they saw too many barriers to uptake. And in this situation where everyone’s really busy and they’re all in the especially in states thinking very, very carefully about how much money and how much time and how many people they’ll need over time. They’re all thinking about losing staff, etc., that it didn’t immediately seem like it was going to boom, withdraw it with geographic atrophy, though it’s a very different situation. So, the geographic atrophy, when I talk with and I’ve been talking with optometrists and retina specialists since about December last year and continuing to get voice of customer input inputs, the word need is coming up all the time, and it’s need those needs that we can address. And it’s those needs that we are addressing and we’re moving towards addressing, but doing pilots in the States early next year.

Robert Klupacs [00:25:24] It’s fantastic. Why we do this podcast. We want to talk to entrepreneurs and try to get as much learning we can for our listeners, which is a lot of budding entrepreneurs, in particular in academics. So in your journey, I mean you the ultimate Start-Up it looks like it’s being quite successful. You go from 0 to 12 people, got investment, you know, breaking into the in the United States, but. If you look back, as you spoke about before, and you had to give advice to someone else who’s got a great discovery, perhaps like you, who was a card-carrying doctor who thinks, ‘gee, I want to be an entrepreneur, I want to have a crack at this”. What have you learned and what information do you think you could provide to people who are coming after you? Because that to me is the learnings of this podcast, because everyone’s coming in a different. But there are some themes that people don’t realise. And as you said before, you didn’t know what you didn’t know.

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:26:13] Yeah, but absolutely, I’ve referred to it as a Rumsfeld journey. The first thing I would say is actually say, read the Lean Start-Up, read it right at the beginning, and it sort of teaches you how to think about things. It doesn’t apply to health that much as easily because this concept of the minimum viable product in the lean Start-Up in, say, consumer electronics or whatever is, is very minimal for doctors and clinicians to use any kind of new something new in their clinical practice. Minimum doesn’t cut it, so it’s got to be higher. I think also the idea would be to get someone who has experience of start-ups and experience of commercialisation in their very early because I, as I said, came from a background that’s very doesn’t really we didn’t really think about commercial things and so I didn’t know about the importance of having, having the, having the ability to or needing to think about the commercial side. So that I remember meeting, I actually flew to Basel and presented to a pharma company. And then when I was asked, What’s your business model? And she didn’t know what they were talking about. It was like really naive. And I think if I had some people who had commercial acumen by my side, that would have been the point at which it took off. It would have been much, much earlier. So Lean Start-Up approach and having commercial people talk with you and having them on board at the same time would have compressed the journey, saved money, and would probably have ramped up investment earlier.

Robert Klupacs [00:28:04] Fantastic. So I want to pivot a little bit because we’ve done a little bit of research on you as well, the binder and you’ve been involved in the Myanmar Eye Care project, which I understand is the only one of its kind in the world. For our listeners, can you tell us what that is and why that’s so important? We’ve I’m not sure we’ve got all the information, but when you were coming in and what is going on there says absolutely fascinating but I’m not sure too many people in Australia are aware of it.

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:28:31] Yeah, this was started by a retina specialist in Sydney Kwan, and he’s not from here by himself, but he thought this was an important thing to do and I 100% agree. I’ve in the past not done so-called missionary work, third world stuff that people use those times because basically it was one of those situations where it was just feeding people, giving people fish. It wasn’t teaching them to fish. And it’s short term, it potentially allows the the doctors to go in as a knight in shining armour and then they leave. What’s amazingly good about the Myanmar projects was that it was about teaching vitriol, retinal surgery. Now cataract surgery has been around a long time and people have gone overseas and taught it. In fact, a lot of cataract surgery done in the developing world, technically, skill wise is significant, is amazing. So, there’s a point at which there’s not that much for people to learn overseas. That is still the case. But in many of the original places I went to retinal surgery and retinal treatments of much more subspecialists, usually about 10% of ophthalmologists or retinal specialists and the type of surgery do, other ophthalmologists don’t. And the idea was for large populations, particularly for things like trauma, detached retinas, and severe diabetic eye disease, that’s a need where people just go blind if they’re not if they don’t have the right surgery. So going there and doing an operation and leaving doesn’t work because most of the hard parts of surgery are the decision making before and the management after. The surgery itself is something you just learn to do over time. So, what that the Myanmar Eye Care Project was we went over and actually had local ophthalmologist who’d been selected to do this surgery and trained them to do the surgery. So, we it was, it was sometimes for us to. It was often frustrating. It would have been so much faster for us just to do the surgery ourselves. But we actually always sat there and taught and sat and watched and taught. And basically, that was in the clinic beforehand, in the operating theatre and then post-operative we would do the same. And that’s the teaching to fish rather than just giving a fish approach.

Robert Klupacs [00:31:07] You’ve done that, you created wreckage and you’ve been very, as you said, you’re treating 8% of the population of Victoria. You’re a busy man to be there. How do you manage your or your time?

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:31:17] Well, COVID, so this is I was referring to this earlier on. COVID told me that you actually have to put time into things for them to work. So I had to make a decision about Macuject and I could see where it was going and what it could do and saw how much it flourished, both with the BioMedTech Horizon’s grant and the time that I and others had to make it happen. So, I had to make a decision. And I’ve basically stopped operating in order to make more time and have compressed my clinical work. So, I’m doing much less clinical work than I did before.

Robert Klupacs [00:31:53] So you might do something because you made a very big sacrifice, because all that training to be a surgeon no longer doing surgery.

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:32:00] Yeah, it is a big sacrifice. And as he put it, yeah, I personally don’t actually miss it that much. I think it’s one of those things where when you’ve done it and done it lots and I was pretty good at it, then you can put your heart, you can just you can just give up and your heart’s up, you know.

Robert Klupacs [00:32:23] The last question. One of those got two more questions for you. But one of them, you know, listening to your story here, the Institute we do with a lot of clinicians. I love the research, but I don’t really want to jump full bore into research. But clearly, you do seem to be able to have bridged the two. And what advice would you give to other doctors, specialists who are fascinated by not by helping their patients, but creating new inventions to help the patients better, but they still want to practice. What advice would you give them?

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:32:54] I would say that even if they’re early on in that or once they’ve got to the point where they know that it’s a good idea and they shouldn’t give up medicine, but they should make time for the extra thing, because I think that trying to say I’ll do it in the weekends and evenings does work. You can make it happen. And we’ve all, many of us trained and worked long hours and stuff, so we’ve done that before. But you don’t get to spend as much time on those things as you might want. I think you should actually time box and create time and just accept that there’s some things you can’t do clinically at times. So many ophthalmologists work in two or three or four different clinics, I would suggest. You just say, you know what, I’m not going to go to that clinic anymore. I’m going to just use that time to do the extra thing. And I think having time boxed or specific time would just make it much easier to do things. I think also they should just do it and try it and I think that’s the difficulty with you asked me about specialists. Difficulty at that point is we’ve most of us been down this very long pathway and on this narrow pathway that we’re just likely to continue on. I think that the time to do that, I’ve done it late. I’m in my late fifties and this is it’s going well because I’ve got the stability of having done my speciality for quite some time. So I’m financially well off and my kids out of university. So that’s easy. I think it’s riskier earlier on. And so that’s why it’s a difficult thing to do but take some time. I think I was reading recently about an approach to career and thinking about it. And there was this idea of that you have these phases every few years where basically you look up and you look at lots and lots of different things around you and try lots of things, and then at some point you think, “oh, well, that one’s the one I find interesting.” And narrowed down onto it and you start doing that for a while and then make sure that you remember to look up after a few years, look around and see what else is interesting, and then choose a slightly different route. In subspecialty medicine, that’s pretty much impossible. In general, practice is good. It’s, I’m sure, possible and in more general jobs as possible. But the most important things start thinking early. So, yes, you’ve qualified as a doctor. Yes, you enjoy it. You’ve been working there for a while. Start looking and consider having parallel careers, not alternative careers, but parallel careers.

Robert Klupacs [00:35:34] I mean, one of the things we want to do with the institute find specialists and offer them the chance to work here a day, a week. Would that be enough, do you think, to get people excited to learn a bit more, to look up, as you say?

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:35:45] I think that day would be a good start and it would be not too much of a commitment. So, they could, after a while, decide, “yeah, actually it’s not for me.” And that’s the other thing I’ve learnt through the rigour and the accountability from doing a grant-based program is actually these milestones or these so-called go no go points. So, if you actually go and if they come here and start working it for a year or give themselves a specific time and go at that point, I’m going to need to decide whether I’m going to carry on doing this. I maybe do it for two days a week or say, I’ll try it. It was not for me and then stop. I think that would be an important thing to do.

Robert Klupacs [00:36:29] One last question, because I know we could talk to you all day, but we’ve got to come to an end. But I think you mentioned earlier AMD’s very large disease is getting more and more people as the ageing population gets older. General advice and general advice. We won’t hold you to it. But what can we all be doing to protect our lives? Much better. Because the last thing I mean, I know surgeons get paid to that’s their job, but probably I suspect most people would prefer that we were healthy, and you didn’t have to treat them. So, do you were there any advice you get to our listeners about what we can do to make sure we don’t get armed or we protect our lives better?

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:37:06] It said that roughly three quarters of whether you get AMD or not is from your genetics. So, you can’t change that. And the rest is lifestyle and other things. So, every time I see a patient who has AMD wet or dry of either side type and I see the patient who’s usually 70 plus and it’s usually come in with a child or carer that’s roughly my age or even a grandchild, I will spend time and talk and explain and talk about macular degeneration with the patient. And then at the beginning of the consultation I’ll ask what the relationship is between the person, the carer and the patient. And if the patient, the carers, a relative, I will then turn to them and basically say the following. And I’ve developed this pattern here in Australia for this reason, and that is you. If you’re the child of someone with wet macular degeneration, I ask them if they smoke, and they say no. I say you’re 27 times more likely than me to get this condition. And if they say yes, I tell them there are 100 times more likely than me to get this condition. If the caregiver is not there, I explain this to the patient themselves and pass it on. I’ve got a leaflet about the next bit, I’m going to say, and I’ve got a website that explains a lot of this too. But what I will then say is, well, you can if they don’t smoke, you can reduce your risk. So, it’s almost the same as mine pretty much. And that’s purely about what you eat. Okay. So, you need to eat if you want to reduce your risk. Fish, green and gold. So, the fish is omega three fatty acid rich fish like salmon, sardines, herring, mackerel. Three times a week or more. You actually have to eat the fish. Fish oil capsules for this condition don’t have any benefit. The green is dark green, leafy vegetables, spinach, kale, or silver beets. But the volume is huge, and this is the difficult part. So, if you eat cooked volume, but you don’t have to cook it one cup a day, five days a week, that actually reduces your risk tenfold. Or thereabouts. Yeah. And then the gold is brightly coloured vegetables, particularly yellow orange ones like pumpkin, capsicum, pumpkin, sweetcorn, squash. And you incorporate that in your diet. So, if you eat fish, green and gold, and then also a handful of nuts or more a week and finally only cook with olive oil, butter, okay. Not canola, sunflower, vegetable oil or rice, bran and whatever, because they have omega six fatty acids which raise your risk of this. So I tell them, I’ll tell patients about this and then and their relatives about this. But if they if but then I also say look, if you have to be honest with yourself, if you’re in the top 20% of people in terms of that, if you actually do that and can do that, then you’re fine. If you’re in the bottom 20% and you’re totally honest with yourself, well, you should probably go and get some supplements. And in between, there’s no really good evidence. But you could argue there’s not much harm done by taking the supplements that are recommended.

Robert Klupacs [00:40:24] I think I saw a stat that the amount of money spent by insurance companies and governments on anti-VEGF factors for treatment of what I am doing is great and $20 billion worldwide and growing. And yet what you just said, if we could convince people from a dietary perspective put all that we could save a lot more money by getting people to eat properly rather than having to treat them at the back end by the end of it.

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:40:46] Absolutely. But instituting lifestyle change is just close to impossible.

Robert Klupacs [00:40:52] I know, but we we’ve got to start somewhere.

Dr Devinder Chauhan [00:40:54] Yeah. No, absolutely. Yeah.

Robert Klupacs [00:40:55] Devinder, We’ve reached the end of our podcast today and I thank you so much for giving us your time and for sharing us your journey. And we’re really looking forward to exciting updates about the success of next year. To our listeners. I hope you enjoy listening and I look forward to introducing you to other guests in future podcasts. There are links to everything we talked about in the show notes, and we look forward to welcoming you next time.

Dr Devinder Chauhan, CEO and Founder of Macuject.

Listen to other episodes of Med Tech Talks here