Med Tech Talks

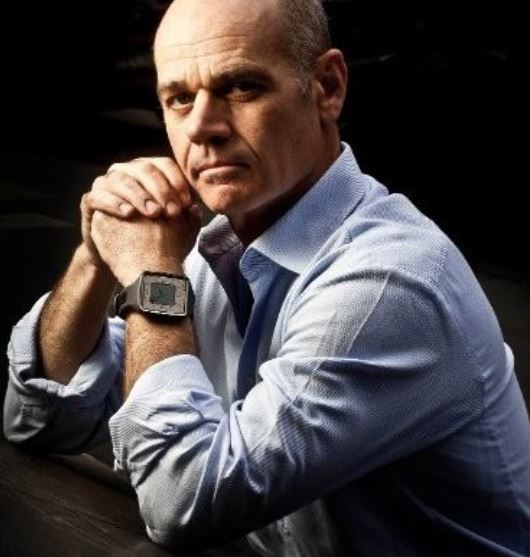

Growing a global business with Trajan Co-founder Stephen Tomisich

Stephen Tomisich, Co-Founder of Trajan Scientific and Medical

Based in Melbourne, Trajan develops and manufactures analytical science instruments, devices and solutions for health care, as well as for food and environment analysis – the only company of its kind listed on the ASX.

Stephen has a strong acquisition strategy, having grown Trajan from a kitchen table concept in 2011 to a global collaborator. Over the last 13 years, Trajan has acquired twelve businesses across the US, Europe and Asia, developing Trajan’s key capabilities and product lines for emerging technologies.

In this episode you will hear about:

More information:

Discover more about Trajan Scientific and Medical

Stephen is a panellist at the upcoming Bionics Institute Innovation Lecture on 29 May in Melbourne. Learn more about the event and register your interest in attending.

Stephen Tomisich [00:01:15] Thank you Robert. Thank you for having me.

Robert Klupacs [00:01:17] We’ve put together a long list of questions because a few people knew you were coming on, hopefully you can answer them all. If you can’t, Will might understand. It’ll be.

Stephen Tomisich [00:01:24] My pleasure. You’ll probably have to interrupt and stop me on the way, I’m sure.

Robert Klupacs [00:01:27] Okay. Stephen, you’ve led trading through an incredibly impressive trajectory, as outlined in the intro. For our listeners who might not be familiar with your company, can you tell us about Trajan’s mission and the solution they provide to the sector?

Stephen Tomisich [00:01:41] Yeah, I’d love to start there. So early on in the Trajan journey, we realised it was about physical tools and analytical data. And what do I mean by that? We noticed that analytical data, information coming out of laboratories that typically use tools like mass spectrometry and chromatography were performing measurements that were increasingly important to human well-being. Now, initially, these were obvious – things like the levels of toxic pollutants in the environment or contaminants in food. But we started to notice that there was more analytical work that was heading towards life sciences. And when you see companies like Agilent Technologies start to appoint Chief Medical Officers, you ask yourself, what’s this all about? And the techniques of chromatography mass spectrometry were being increasingly used in fields like theomics. So we start to think about these processes that generating analytical data and data therefore can become more important. What’s what’s the key thing here. What is it that might cause a variation or give people confidence in data? And we noticed that many products involved in chromatography mass spectrometry that used to be considered commodities were now becoming more important. And what I mean by that, if we look at where does uncertainty come from in that workflow, it starts to become simple things like a glass tube or a connection, or an injection device, or the surface chemistry on a microfluidic chip. And so what does Trajan do today? We focus on those components and consumables that touch that sample. And that sample might start off as a drop of blood, a sample from a river stream, it could be a food material. And we focus on how do you make the most precise devices, how do you make the most inert chemistry surfaces because it’s about physical precision and chemical and nutrients that then underpin the quality of that analytical data that ultimately is used in information and decision making. So that’s a long, long answer. And I give you the long answer, because if you look at our portfolio, you say, oh, look at this company. They make syringes and glass tubes and connections and all these sorts of things that seem like it’s a Turkish bazaar, if you like, of a suite of products. But there’s actually a common theme and a strong intent behind all those things that we do. And that is: how do you make the best ones in the world that ensure the quality of the analytical result that the scientist is going to generate?

Robert Klupacs [00:04:21] And you do a lot of innovation in house or do you see what’s you need for what’s going to happen in the future when you go and acquire that technology. What’s your model?

Stephen Tomisich [00:04:30] It’s a combination of both. So if I think about some of the glass products, after we had acquired the analytical science business here in Australia, we were fortunate enough to be supported by the federal government with the Next Generation Manufacturing Grant. And we channeled all those funds into glass tubes from the nanoscale to the millimetre scale and thought about, how do we create production fabrication processes that would allow us to produce these components or these consumables the same way every time, with great physical precision. Equally, some of the acquisitions we’ve made for example, in 2022 we acquired CRS in Louisville, Kentucky. They are the best by far at some other elements of the chromatography workflow. Simple things like silicon chemistry. But again, the quality of what they do has a significant impact on the underlying quality of the analytical data. So Robert, it’s a combination of both. How do you develop and refine processes, particularly fabrication techniques. And at the same time are there areas where you need to go out and find who is the best at the world, at what they do, and then combine that with what we’ve already developed in-house.

Robert Klupacs [00:05:44] Well, that’s an amazing story. I don’t think anyone looking at Trajan listed on the ASX really understands the thought that’s going on behind it, I certainly didn’t. Thanks for clarifying.

Stephen Tomisich [00:05:54] I’ll just I’ll just make a comment on that. Right. We absolutely welcome people to come and visit at Ringwood here in Melbourne. And one of the things that I say to visitors is if you look at our catalogue, if you look at our website, at first glance, you’ll think, wow, thousands of products here. How do you guys manage? In Egypt such diversity. And I’ll say them. Forget all that. Think about a glass tube. Now walk and have a look at this facility. And what you actually see is glass tubing of all different physical styles, right down to a five micron idea to a millimetre idea. That is then being coupled with whether it’s plungers or connection devices. They might have features added to them, but the core competency is in how you fabricate precisely those glass tubes that then go on to become part of a device or analytical component. Robert Klupacs [00:06:47] It just takes…for listeners.. Let’s just take a step back. Let me take us back to that pivotal moment when you and your wife, Angela, decided to venture into your own business, specifically within the med tech sector. What motivated you? You’re you’re an intelligent man. What what motivated you to take that leap of faith?

Stephen Tomisich [00:07:04] Yeah, I’m an intelligent man. And maybe in reflection, we might want to revisit that. I can remember that moment with great clarity. And to me, what it was all about was identity. We do reach stages in life where you stop and ask yourself, well, who are you really? You know, who are you? And what I found was that there was a growing gap between the narrative in my head of who I thought I was and what I thought I was capable of compared to what I was actually doing. And… It was that moment, and Angel and I both had significant birthdays that year, that we both said, if we’re going to bridge that gap, if we as human beings on this planet are going to realise our potential, if not now, then when. And we went through various options. We said, you know, it’s okay to just continue our corporate careers as we had always involved in the global world of analytical science. Angela was involved in biomedical science and particularly clinical trials here in Australia. We contemplated, should we take a year off? You know, that was really tempting. Let’s just take a year off and find ourselves. But both of us are probably way too impatient to entertain that as an option. Or we said is it now time to actually go out into the world and see what we can achieve? What difference can we make? And we had flirted before with buying little businesses. In fact, at one stage we bought a little retail business, and I did that because I want to see whether my understandings of business strategy, customer behaviour were translatable from what I had learned in my corporate life to things like a little fashion store. And indeed, you know, they were. So you do little experiments like that and it gives you a sense of confidence. We flirted with some other businesses. We looked at at a dentistry business at one stage, but we also came to the conclusion that at that stage of life, if we were going to literally roll the dice and go and do our own thing, then we needed to take the equity with us. Where was our competency? What did we know about the world that we could use as a platform and go on and do this? And I know it’s a long-winded answer to your question, but, you know, to continue on. We also realised that stage of life that if we did this and used every ounce of what was relatively modest wealth at that stage to pursue this goal, if we completely failed, were we young enough that we could start again? And the answer was yes. And so therefore, the two of us and my daughter Danielle was at the kitchen table as we had this discussion, we said, well, we’re going to do it, then it’s all in. It can’t be a sort of quasi decision. It can’t be a partial commitment, it has to be a full commitment. And we even went to the extent of going across the road not long after talking to our neighbours and said, here’s what we’re going to do. We don’t know how it’s going to start or what we might call the company or where it might go, but if we actually end up losing everything and we become personally bankrupt, can we move in with you for for a period of time until we get back on our feet? And every now and again, we still have dinner with those neighbours occasionally. And they remind me, you know, of that story. But it wasn’t in jest.

Robert Klupacs [00:10:28] They probably really relieved.

Stephen Tomisich [00:10:30] I think they quite relieved. I haven’t relieved them of the responsibility, although I have no intention of ever needing to call upon that wonderful favour that they said they would agree to.

Robert Klupacs [00:10:39] That’s that’s a really interesting insight because one of the things is common – we talk to entrepreneurs like you – I’m not sure I can ever be one because they have to take that risk. And the ones that we’ve spoken to have been successful. And Sam and I have spoken to about 30 now; it’s the only… is exactly as you said, you can’t be part pregnant. You’re all in or not in. And that’s the thing that’s coming out from all these interviews we’ve done. That’s why I’m so full of admiration, because not everyone has been successful.

Stephen Tomisich [00:11:07] Yeah, that is such an important point, Robert. At one point in the Trajan journey, we thought we could replicate this. We could create our own little innovation hub and run an accelerator model. And so we entertained about 14 different little start-up businesses where I thought I could apply the same thing in game. And in general it was a failure. And the key reason it was a failure was exactly the point you made then, that you’d end up speaking to people who wanted to be CEOs of their own little business, who wanted to be entrepreneurs, but frankly, not all in; not 100%. They wanted to keep their daytime job as well. Right? And I would try to say to them, “but if you’re in, you’re in”. And I think the second part of the equation is you got to have purpose and passion. That being an entrepreneur wanting to run your own operation isn’t about what it does for you. It isn’t about your story. And are you going to create wealth out of pursuing this activity? It has to be that the activity in itself has a purpose that is delivering value to a people, some somewhere. And then, you know, good old Steve Jobs will… You have to be passionate about that purpose to the extent that you’ll do things that sane people won’t do.

Robert Klupacs [00:12:35] Yeah.

Stephen Tomisich [00:12:36] Because ultimately that’s that’s what it requires. And I think one lesson I’ve learnt on the Trajan journey, you know, you hear all these, you know, these stories and these throwaway lines. But one of the things that I think I have learned is that it is true that if you are persistent, you will succeed. That you have to always think that there’s another way to solve a problem, whether you go over and around, turn it upside down, think back to front and you only get to that type of decision making logic if you’re all in, if you’re passionate, if you have a purpose. If there’s an out, an easy out, I don’t think you push through those really, really hard moments, those really tough calls where you have to find a way to solve the problem. Because if you don’t, you’re gone.

Robert Klupacs [00:13:23] You’ve almost pre-empted my next question, which were written down beforehand, because it comes from there, actually. So we were reading about your journey, and you’ve been pretty open about the difficulties. You just touched on, some of them having to be all in, and the fact that you and your wife didn’t take any dividends from the business for over ten years, only a salary. And I understand reading the annual reports a relatively low one as well, and then reinvesting everything back into the company. Can you just share, you know, for our listeners and we’ve got lots of budding entrepreneurs. Just tell us how hard that was and what made you make those decisions.

Stephen Tomisich [00:13:57] I think it comes back to the business having its own identity and its own life. I have seen occasionally Founder Owners, family-type businesses where the business is a means to an end. Its services and income may a family goal of some sort rather than the business – the activity – having a purpose in its own right. And when that becomes the greater purpose, then you to treat it as the greater purpose, right? And therefore you think, okay, what do I need to get by? But in the meanwhile, I need to feed the beast because the purpose is succeeding. And in and you know, success breeds success. So you do a few things and they work, well, if I can refer kindly to Trajan or our business as ‘the beast’, its appetite grows.

Robert Klupacs [00:14:47] Yep.

Stephen Tomisich [00:14:48] And so you continue to double down in good old Jim Collins language. One of my favourite authors, by the way. You continue to double down on the things that work, and it becomes sometimes an insatiable appetite for, you know, doing the next right thing. And I think that’s part of it. I think the other part of it was that from the moment we started Trajan, I was conscious that we weren’t in our 20s. And so I’ve been quite impatient all the way along with an underlying feeling that if we have started this too late in life, then we haven’t got time to stop.

Robert Klupacs [00:15:23] Yep. Stephen Tomisich [00:15:24] You know that. Therefore keep, keep it fuelled, keep it going, keep running hard and continue to achieve the potential while we can.

Robert Klupacs [00:15:31] Yeah. Next question again. You. You’re pre-empting all my question, which is wonderful because you just talked about that feeding the beast. Yeah. Sam and I have been doing some research and we might have gotten this wrong, but what we identified is that Trajan has acquired at least seven businesses over the last thirteen years, which is huge by anyone’s standard. You’ve also got an emphasis on organic growth. And so you alongside acquisition. So that’s a big job. So how do you balance maintaining the integrity of the acquired businesses with aligning them with your vision for the company. And then as you say, feeding the beast to make them better.

Stephen Tomisich [00:16:07] Yeah. So we acquired the seven prior to IPO.

Robert Klupacs [00:16:10] Right.

Stephen Tomisich [00:16:07] And that was out of our own cash flow. And post IPO we’ve acquired another five. So we’re up to twelve so far. And I think sometimes it’s one of the misunderstandings about our business model that sometimes people think, oh, okay, this is just an M&A model, it’s a roll up, buying businesses. He’s kind of put them all in a stable and then, you know, somehow market it off to, you know, some other suitor. And that is far from the truth. That what we’ve actually been doing is we’ve been saying, following our purpose, following our vision. Coming back to the opening comments about the importance of data. We’ve looked at the total workflow. How is a sample collected, how is it processed, how is it measured in an instrument? How does it become… translate into data and then actionable information? And as we map out that workflow, we’re asking ourselves all the gaps. How are we going to fill them? Do we need to develop them in-house? Do we need to acquire them? So as we’ve gone on this acquisition trail, it hasn’t been necessarily about buying businesses. It’s been about looking at key capabilities or key product lines that fill another gap in that end-to-end workflow. When we do identify a target, you know, like that and we bring them on board, my logic, again is probably opposite to the MBA logic. And my logic is that first and foremost, you think about people and culture, and the rate that you can absorb and integrate a new business is determined by the tolerance of the culture that you’ve encountered with that target. You know, I have some great examples recently where we’ve acquired businesses in parts of the US, the culture – extremely tolerant to rapid change integration. Some of those businesses with integrated within the first month without any, you know, business loss. There’s been others that we’ve acquired in other parts of the world, like Germany, where it’s been a multi-year process, step by step, methodical to ensure everybody is on board along the way. And as we go about that integration process, I don’t focus on the bottom line. Shock, horror to the whole investment world. I don’t focus on the bottom line. First and foremost, I focus on the top line. If I bring a team together at a journey with my team here in Australia together, how can we grow? Ask the positive questions first, and so the teams look at each other and think about how can they help each other? How can they together win new customers? How can they provide deeper, more meaningful solutions to their existing customers? And so you start to have this positive interaction as the marriage begins. And over time, and it’s not a lot of time, it can be 12 months, 18 months. The synergies, the duplications in the back office and those sorts of things, they become obvious to everyone. And then you get buy-in as to how we would resolve those particular issues along the way. And that’s worked for us thus far. Focus on the positive synergies first and over time, then realise the cost synergies, the back office synergies.

Robert Klupacs [00:19:26] And one of the questions that I always wanted to ask you is you’ve grown with not seven but twelve companies lots of time, Angela and you are impressive people, but you’re only two people out of 450. How much is your time is taken to actually put your DNA into the new acquisitions? Or have you been able to just develop a culture internally that other people bring to the new acquisitions for you?

Stephen Tomisich [00:19:48] So for each acquisition, we think about who’s going to lead that. And in no case is it me.

Robert Klupacs [00:19:54] Right.

Stephen Tomisich [00:19:55] Now, if I think about Louisville, Kentucky, one of my key managers, a lady based in the UK, she led that one. If I think about the acquisition of LEAP PAL Parts in North Carolina, my head of commercial team based in North Carolina, he led that one. And so the team, the M&A team that takes care of the services, like how are we going to integrate financially from an I.T platform, branding and marketing; they’re a common team that are getting pretty good at this algorithm, if you like. But in each target it’s a different person who has led that initiative. And yes, I oversee it, but my management style is very much hands off. People know if I’m into the detail, something’s wrong, and that’s probably when I do get into the detail. If I think about what’s been delegated and how people are operating, I always map out what’s the worst case scenario. If this all goes wrong, how bad could it be? And if I don’t like the answer that question, that’s when you’ll see my sleeves come up and I dive in into the deep end. But I’ll just make one other comment on the acquisition strategy, and that is that we never bite off more than what we can chew, swallow and digest. And you’ll notice, therefore, that the types of acquisitions we’ve taken along the way, they’ve been at most, you know, a quarter or a third of the size of Trajan, what I refer to as the mothership.

Robert Klupacs [00:21:22] Yeah.

Stephen Tomisich [00:21:23] So I never think about acquiring something that would put the core business at risk. Always something that if we bring all our resources to bear, that we’ll find a way to ensure that we’re able to absorb it, integrate it, without threatening the continuity of the main business.

Robert Klupacs [00:21:38] And how do you sell yourself to those as acquisition targets? So you can imagine these people working in Kentucky. Very proud of the fact that you can recognise some of the best of what they do in the world. And then this interloper from Australia gives them a call, says, “would you like to be bought?” What’s the process? What happens when that call happens?

Stephen Tomisich [00:21:52] We’re very fortunate in that and with so many years’ experience in this industry, the majority of our acquisitions to date we’ve known, and if I look at my current opportunity list, we know most of them. What’s happened in the industry is Trajan’s come along as this new alternative, as a landing place for founder-led business, their businesses to have some speciality, some niche in their industry that’s caused them to survive for a period of time. And when those founders are looking for an exit, often they don’t want to get involved with an investment bank and do an IM and run a process. Nor do they necessarily want to see their legacy end up in the hands of a large multinational, where it runs the risk of being lost along the way. And what we offer is an alternative to this in the middle. That we’re able to globalise their business, we’re able to honour their brand. In many acquisitions that we’ve made, in the facilities that continue to operate, we will rename the boardroom after the Founder. So, for example, here in Ringwood, it’s the Earn Doors boardroom. In North Carolina, it’s the Werner Martin boardroom in Connecticut’s Jim Bray boardroom in CRS, it’s the Glenn Thomas boardroom. And I honour those people because they did something that I can’t do. They started the business from nothing, from scratch. I’m okay in terms of having a going concern, thinking about how can you improve it, how could you marry it with something else, how could you introduce new products to it? But I have a real respect for those real, what I would call the real founders, who are people who start with absolutely nothing and create a new product and provide a new service to the world.

Robert Klupacs [00:23:41] Just as a fantastic story, I’m glad we’ve got it on tape so everyone can hear it. Your story is interesting because you spoke at the beginning about glass in all shape, and no one really thinks of glass as innovation, but clearly there’s been a huge amount of innovation. Go behind that. We love to talk in this sector and this talk podcast about what that means. And from your perspective, you’ve got places all around the world that you’ve acquired. You’ve worked with big companies. As a CEO, what strategies have you implemented to foster innovation within the company and stay ahead of the competitors? Who’re snapping at your heels every day.

Stephen Tomisich [00:24:16] Yeah, yeah, I think this several parts today. It’s and is probably no surprise that it’s a multi-tiered response to that to that question. The first part is embedding a culture that it’s okay to fail. Angela and I spent four years living in California, and I think one of the things that got embedded in our heads living in the US was you be asked, what have you failed at? That it’s okay to fail. And sometimes in the Australian culture, we have the opposite point of view. One of my favourite authors that I mentioned earlier was Jim Collins, and one of his philosophies is fire bullets and then fire cannons. That is a philosophy of failure. What it means is have a go at many things, just a little bit, and think about the things that resonate, the things that seem to work. Kill all the others off and then double down on the one that has merit. That you’ve heard the voice of the customer say, there’s something to this. And we’ve done that the whole way. Along the Trajan journey, we have far more failures. I have failed at far more things than I have succeeded at. And but I think that’s part of what the culture needs to be in order to, to be successful. The next part of the answer is that… I try, and I encourage my team, to try and think about innovation beyond technology innovation. Think about holistic business model innovation. One of the things we realised in the Trajan journey a number of years ago, when we had a session exploring what was our core competence, was our core competence actually wasn’t a technology competence, it was a business model competence. And the core of that was the ability to collaborate. And so we asked ourselves, you know why? Why was that? And it came about because we were privately held and therefore agnostic in the industry, that because lots of our operations were highly vertical, it meant we had control over product form, fit, functioning, ways that could be crafted around particular target customers and what they wanted to achieve in their business models. But also because we were global. And you bring those things together and you start to have this company profile as being a capable global collaborator, which then allows you to think about very, very different business models. The final part of the answer, and it’s something that we still need to improve at greatly, is don’t start with the solution. Start with the problem. That if I go back to one of my other favourite authors, Jeffrey Moore, and I was fortunate enough to see him in person in the US when he first released Crossing the Chasm, that is now, you know, such a standard business model, you know, adoption model for new technologies across so many industries. That, number one is what is your value proposition? But expressing it in terms of: what problem are you solving for who. And then look at what is the innovation behind the development of that solution. It’s another observation I would make that still often I see potential start-ups and entrepreneurs starting with a solution, looking for a problem, you know, and maybe that works sometimes, but in my experience, the most valuable outcomes are where there is a problem and you develop the solution.

Robert Klupacs [00:27:49] You make it sound so easy, Steve.

Stephen Tomisich [00:27:52] It aint easy!

Robert Klupacs [00:27:56] Well next question. So as you made it simple for me at the beginning, you said everything comes back to glass, but it’s all about the sample and integrity of the sample. But clearly, there’s different types of products for different needs across different sectors. You bought twelve different companies who are specialists in this particular area. But I’m assuming that the regulatory system, because you’re playing in a highly regulated system, is different across your product lines. How do you navigate that now across the integrated companies and yourself in your innovation chain? And your supply chain.

Stephen Tomisich [00:28:26] Yeah. It’s not only the regulatory setting but also compliance as well. And the onus that’s it’s very onerous now on on businesses when you’re trying to compete worldwide. Of all the various areas and I mean the latest wave of course is ESG. Yeah I know. And before that it was modern slavery and before that was conflict minerals and before that was Ross and Reish. And of course, then we get into the medical regulatory, space. Fortunately, because we’re in the analytical science field, not a lot of what we do crosses into the medical device regulatory space. Having said that, we do very much deal with that on a regional type basis, and we have our own regulatory person who’s familiar with the FDA sitting on the east coast of the US, managing all of that, arrangement and doing it across the business. So whether it’s for our pathology business or our micro sampling business and some of the other areas that are on the cusp of, you know, servicing an analytical workflow, but being a medical device. So we sit right on that, you know, barrier or that boundary line there, that they are performing that that role for us. But again, it is also about having people in the local markets that understand the local systems, processes, cultures that you need to work with.

Robert Klupacs [00:29:50] Yeah. You mentioned earlier, I’m trying to make it simple, think of glass for your business. What’s the black swan that could just disrupt you and you have to think about every single day?

Stephen Tomisich [00:30:01] So in my philosophy of worst case scenario, I think about that every single day. And maybe come back to the earlier comments about, you know, being all in. Yeah, I still don’t have a night sleep where I don’t contemplate, how could this all fail? How could all go wrong? And sometimes I kick myself and I think I’m stupid. And then I’ll go and watch another wonderful, inspiring Steve Jobs video that says, you know, if you’re not worried about your business every day at night, then you’re doing something wrong. I think I mentioned earlier, today that if you’re getting too comfortable and then something is wrong.

Robert Klupacs [00:30:38] Is it as simple as if someone is some, let’s say large country decided to lock away all the sand in the world you’ve been.. that would have been your problem.

Stephen Tomisich [00:30:47] The funny thing is, I visited one of the, glass manufacturers that we work with in Japan. I said, where does your sand come from? Where do you think?

Robert Klupacs [00:30:55] Japan.

Stephen Tomisich [00:30:55] Australia. So we’ve we’ve cornered the sand market, but, you know, circling back to a serious answer to your question, I looked at some of our key revenue generating product lines, and I have put together black ops teams. And I’ve said, if you want to make this technology redundant, what would you do? And they work on making us redundant. My philosophy is that if there’s a threat out there, then become your own threat. I had a wonderful meeting with my daughter this afternoon who was in in the business and up to her eyeballs in the business, and we were talking about a particular enhancement of a product that we could make, that would cause the product to extend its lifetime significantly. And she made the comment as you would normally would. Well, won’t that cannibalise some of our existing business? And I said to her, better that we do it than somebody else. And so, you know, that’s been my philosophy is instead of waiting for the threat to emerge on the horizon, if we know this world and this business as well as anybody else, let’s contemplate how could we create that threat? How could we be that technology, that solution that that makes us irrelevant in some shape or form? One of the things that is nice about the core Trajan business today is a lot of it is based on standardised platforms that exist in hundreds of thousands of laboratories around the world. And it’s in nobody’s interest to go in and turn that world upside down. And 90% of our recurring revenue is coming from that install base. So we’re also not reliant on new instrument sales to capture that revenue. And that gives me a little bit of peace at night. And so I do get a few hours of good sleep overnight. But, it’s it is an observation that I make of myself that I have never stopped worrying about what could go wrong.

Robert Klupacs [00:33:01] You know, I think you’ve articulated best of anyone we’ve had on the, on the, on the podcast, but everyone says something similar. You know, they they never stop. There’s always they always know that they’ve innovated to get to that point. There’s always someone that can innovate better than they have. Yes. So they they’re worriers.

Stephen Tomisich [00:33:18] Yes, yes.

Robert Klupacs [00:33:19] I think now I know I’m not an entrepreneur.

Stephen Tomisich [00:33:22] And I think the thing that can catch you out sometimes is the real threat comes from an adjacency. That sometimes the threat isn’t actually under your nose, it’s your next door neighbour that you’ve never paid attention to. And so I try to be mindful about that as well. If we look at parallel industries, if we think about, you know, we do a lot with chemistry and chromatography. So I asked myself, what’s happening in spectroscopy or what’s happening in the consumer world that could potentially represent a threat? So I think that’s important as well, that you don’t just stick in your lane when you’re looking for threats. Because if we read the history books and think about businesses that we’ve known well, that have been, you know, gazumped; often it’s by a player coming out of left field, not actually in the field that they were in to start off with.

Robert Klupacs [00:34:08] That’s a really good point. You know this next question is coming up because I know you’ve listened to the previous podcast and we love talking about mentorship. We ask everyone and we want to ask you. So to all the young innovators listening, what do you think makes a good mentor and who should they seek out? And we’d love to know who your mentors were, Steve.

Stephen Tomisich [00:34:27] So I’ll give you two parts to to that, question. The first part is, I think the best mentor I had in my career was a gentleman by the name of Peter McIntyre. And so when I was based in the US and had a senior role in the spectroscopy business, he had a senior role in, in the chromatography business. And later on in life, we both ended up in another organisation and he recruited me and I was reporting to him. And what caused me to shine under Peter was that he always saw the best in people, and he was extremely talented at making people realise their own strengths, their own capabilities, that they could bring suit to a situation. And the way that he would critique their weaknesses was subtle, but to the point. And so you come away from the meeting with Peter, and it’s only after that you realised it was a criticism in there, because at the time it didn’t really feel like it, because you were so up. As he reinforced the positive things that you brought to a situation, in your behaviour, or the way you went about solving a problem, whatever it might be, you know? And so I miss him dearly. He was a great mentor for me. And sometimes even today, if I’m in a situation, I think if I picked up the phone and called Peter, what would he say? Well, what advice would you give to me? The second part to the question, Robert, is that when we went on this Trajan journey, for me, part of it was an experiment, and it was an experiment because I had observed some of the business philosophies of people like Jeffrey Moore and Jim Collins, Stephen Covey, and admired their logic around how you should think about business, how you should make decisions. But found it frustrating when I was in the corporate world, never being able to fully execute some of those things. Whereas within Trajan, I’ve been able to do that. And so if I’m thinking about mentorship and guidelines in terms of how to go about making business decisions and how to operate, I call upon my my four favourites. One is that, you know, Stephen Covey’s seven Habits of Highly Successful People is equally applicable to business. So take your personal situation out of that picture. And now think about those seven questions from a business perspective. First things first. Right. Start with the end in mind. All of those principles apply to business as well. Going through Jim Collins book. You know, Good to Great, Great by Choice. There’s some wonderful models in there. I don’t use them all, but I experimented with many of them and said, yep, some of these don’t work for me, but some of them do work really well. Use those. Jeffrey Moore – Crossing the Chasm – yet again. Take some of that what was there. But now use different elements of that. And the last one: Chan and Blue Ocean strategy. And that one I think is highly valuable, particularly for entrepreneurs. When you’re contemplating not just going into an existing market and doing the usual metrics around, okay, how big is the market, what’s addressable, what share can we get? But instead of that, what is called a red ocean strategy, the blue ocean strategy is how do you create new markets for unmet needs. And one of the things I love about Chan’s writing is that it’s about real examples, not just about theoretical examples.

Robert Klupacs [00:38:03] One last question for you. You’ve been a great success story, but your model in the Australian setting is not common. I think internationally I’ve seen other companies do what you’ve done, but in Australia is very uncommon. Why do you think Australians don’t look at you and think that’s a great model to follow, and actually use that as a template to create critical mass that they can take to the world rather than staying just in Australia.

Stephen Tomisich [00:38:25] It’s a very good question, and I’ll be measured in my response, because it’s one of those questions that can often get me up on my on my soapbox. I have to say,

Robert Klupacs [00:38:34] That’s okay. We’re giving you a soapbox.

Stephen Tomisich [00:38:35] Maybe this is my soapbox. Make me perhaps answer the question with a question. What is it that we reward in the Australian ecosystem around innovation and development? Do we reward the development of sustainable, long term, growing businesses, or do we reward speculation.

Robert Klupacs [00:38:57] Or build on speculation?

Stephen Tomisich [00:38:58] And when that speculation fails, who pays?

Robert Klupacs [00:39:03] The speculator.

Stephen Tomisich [00:39:04] The taxpayer. And when that speculation succeeds, who wins? The international company that comes along and buys that wonderful new start-up. So this is my little, little soapbox that if we want to change the ecosystem here in Australia, I think we have to rethink what is it that we want to support to create domestic, long term, sustainable businesses that give us, as we’re all referring to now, sovereign capability? Well, why do we think it’s not here? All right. How do we how do we do that in a way that says we want businesses to be here, employ Australians, grow the skills, grow the sovereign capability? I get criticised sometimes for this point of view, as you know, being corporate welfare or something out of that regard, but it is businesses that create innovation. It’s businesses that create jobs and sustainable economic growth. And I would like us to think more favourably about that.

Robert Klupacs [00:40:09] Have you had the chance to talk to the Innovation Minister, or the senior members of government with this story? Knowing you, you’re not shy, not backward in coming forward. But have you had that discussion?

Stephen Tomisich [00:40:19] Well, perhaps I’ve chosen to do it by example.

Robert Klupacs [00:40:21] Right.

Stephen Tomisich [00:40:23] You know, we we are the only company, the only business in our sector on the ASX. And why is that? If Australia has a history of innovation that brought about Techtron, which became Varian, which became Agilent; or Vision, which became Danaher or others that grew up in this area. Why is it that we’re the only one?

Robert Klupacs [00:40:47] Because of you?

Stephen Tomisich [00:40:49] Well, and I’ve mentioned. I’ve had people knocking on the door. Right. And. I wanted to see. Can we reverse that model? Is it? Is it possible that an Australian business could do similar things to what we’ve seen international businesses do in our sector? And I think thus far the answer is is yes, but not necessarily in an environment that is highly supportive of that.

Robert Klupacs [00:41:16] Hmm, well it’s almost a it’s a sad way for someone to end the talk. But it’s a, a a realistic way to end. And we know that you’re going to continue on with your journey and go from 12 to 24 to 36 and become a behemoth. And we wish you great luck. Stephen, it’s been a joy to talk to you today, have been wanting to have this chat for a very long time, and we really enjoyed your insights. And I suspect if we could have, we could have gone for another 30 minutes at least. And I would have loved to find that the other ten authors that you’d read that that give you a business strategy. To our listeners, I hope you enjoyed listening, and I look forward to introducing you to our guests in future podcasts. There are links to everything we talked about in the show notes, and we look forward to welcoming you next time.

Listen to other episodes of Med Tech Talks here