Med Tech Talks

Innovation Lecture Special

Hear how we can bridge the gap between research and commercialisation from our invited expert speakers and panelists:

In this special episode, you will hear from:

Greame Clark [00:00:30] When did you become deaf? Where do I live? I knew the cochlear implant operation on Rudd was a success when we developed a speech code for electrical stimulation brain that enabled him to recognize some words without any help from lip reading.

Greame Clark and Rod Saunders[00:00:52] Can you hear me now? Is it loud enough for. In the end. In the end.

Greame Clark [00:00:58] I was so overcome with emotion. I went quietly into the next room and burst into tears of joy.

Voiceover [00:01:10] The Institute opened its doors in 1986 and undertook research to improve the cochlear implant commercialized by Cochlear Limited. The implant has given hearing to more than 600,000 people around the world.

Greame Clark [00:01:25] The creation of the Bionic Ear Institute allowed me to coordinate my professorial duties as the head of a university department with that of a research institute. Our coordinated research made significant progress and the Bionics Institute has continued as an excellent participant in Melbourne’s overall research effort.

Voiceover [00:01:51] At that time, bioengineering was in its infancy with a divide between physiologists and engineers. But much has changed in the field.

Greame Clark [00:02:01] There is now a meeting of minds in engineering and medical biology. Engineers now have a good understanding of medical biological problems and vice versa.

Voiceover [00:02:14] The fertile ground for innovation in bioengineering, fostered by Professor Clark at the Bionics Institute, has led to a new approach to Parkinson’s disease. Deep brain stimulation treatment. The design of electrodes in the Australian bionic eye, development of the AP minder epilepsy monitoring device and a vagus nerve device which shows promise in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease and type two diabetes. Our deep expertize in hearing research at the Bionics Institute has given rise to a revolutionary new test for infant hearing, a test for tinnitus that lays the groundwork for new treatments. Research into the genetic modification of nerve cells to respond to both light and electricity and the development of therapeutics to use nanotechnology to restore age related hearing loss. We are honored to continue Professor Clark’s legacy of innovation in the creation of medical devices to treat challenging medical conditions. And we welcome you to join us on the journey.

Robert Klupacs [00:03:39] Welcome, everybody. I’m delighted to have you all here with us this evening to the Inaugural Policy Institute 2022 Innovation Lecture. We thank you all for joining us to hear how strange innovation can build our country, an impact on human health and well-being throughout the world. Picking up on the legacy of people like Graham Clark. Let me begin by acknowledging the people of the Corn Nation as traditional custodians of the non lands we made on today. We pay our respects to their elders past, present and future. Before we jump into this, a few housekeeping items. I won’t ask you to switch your phones off, but I would ask you to keep them in silent mode. You will need them if you want to ask questions via Slido, which will use the questions following the keynotes panel and the panel speakers. There is a QR code on the programs that you got when you came in which will link to the app. You can use Slido to either ask questions or upvote or question during the event. Please make sure that you name the panelist you like your question to be directed to. We invite you to join us for drinks and canopies after the event. Will you be able to meet tonight’s presenters and panelists as well as some of our researchers from Bionics Institute and our sponsors in the May take showcase outside? So why are we here at the Innovation Lecture? Australia is known as a nation of inventors, as she saw the cochlear implant developed at the University of Melbourne in the Bionics Institute over 40 years ago. The CPAP technology developed by ResMed and the HPV vaccine developed by Ian Frazer and CSL are very well-known examples of Australian innovation which has been successfully translated. These life changing inventions have been a significant contributor to Australia’s economy, providing jobs and wealth. However, these successes hide the fact that Australia’s performance in translating our innovation is suboptimal. The most recent report from the Global Innovation Index ranked Australia 25th out of 173 countries for innovation, but only 78 for knowledge diffusion. A proxy for translation. This is despite Australia being ranked number one country in the world for years of schooling. As world leader in the development of medical devices, the Bionics Institute is passionate about and dedicated to improving the translation of Australian innovation. Our hope in creating this event is that by bringing together leaders in the medctech, biotech and life science ecosystem to share their journeys and insights with the broader community, it will provide inspiration for other innovators, entrepreneurs and backers to follow. We are extremely proud that the event has been supported by some magnificent sponsors who have a focus on innovation. We’d like to thank our major sponsor, NAB Health. We’re delighted to welcome the NAB team here tonight and look forward to a long and mutually beneficial relationship for many innovation lectures and initiatives to come. We are also extremely proud that two of our major sponsors of this event, Neo, Bonica and Darby’s technologies are successful. Spin out companies from Bionics Institute. Tonight you’ll be hearing from two keynote speakers from two ends of the Australian, from the Australian startup and an ecosystem. I’m honored to welcome Dr. Andrew Nash, Chief Scientific Officer of CSL and Honorary Associate Professor at the University of Melbourne. Andrew has had a hugely impressive career, spanning a day in immunology, groundbreaking veterinary research, research head and subsequently CEO of ASX company and renamed Zenith and for the past 16 years a stellar research career at CSL. Its chief scientific officer is Cecil. He’s leading a global effort to develop new medicines to treat serious disease. I know Andrew fairly well. We work together. He has lived and breathed the innovation translation journey at startup early stage and major company level. Tonight, Andrew will outline some of his personal journey and learnings, his thoughts and experiences on how we might bridge the valley of death between research and commercialization and some of the major initiatives that CSL is making in this regard. Please join me in welcoming our keynote speaker, Dr. Andrew Nash.

Dr Andrew Nash [00:08:51] Thanks, Rob. All right.

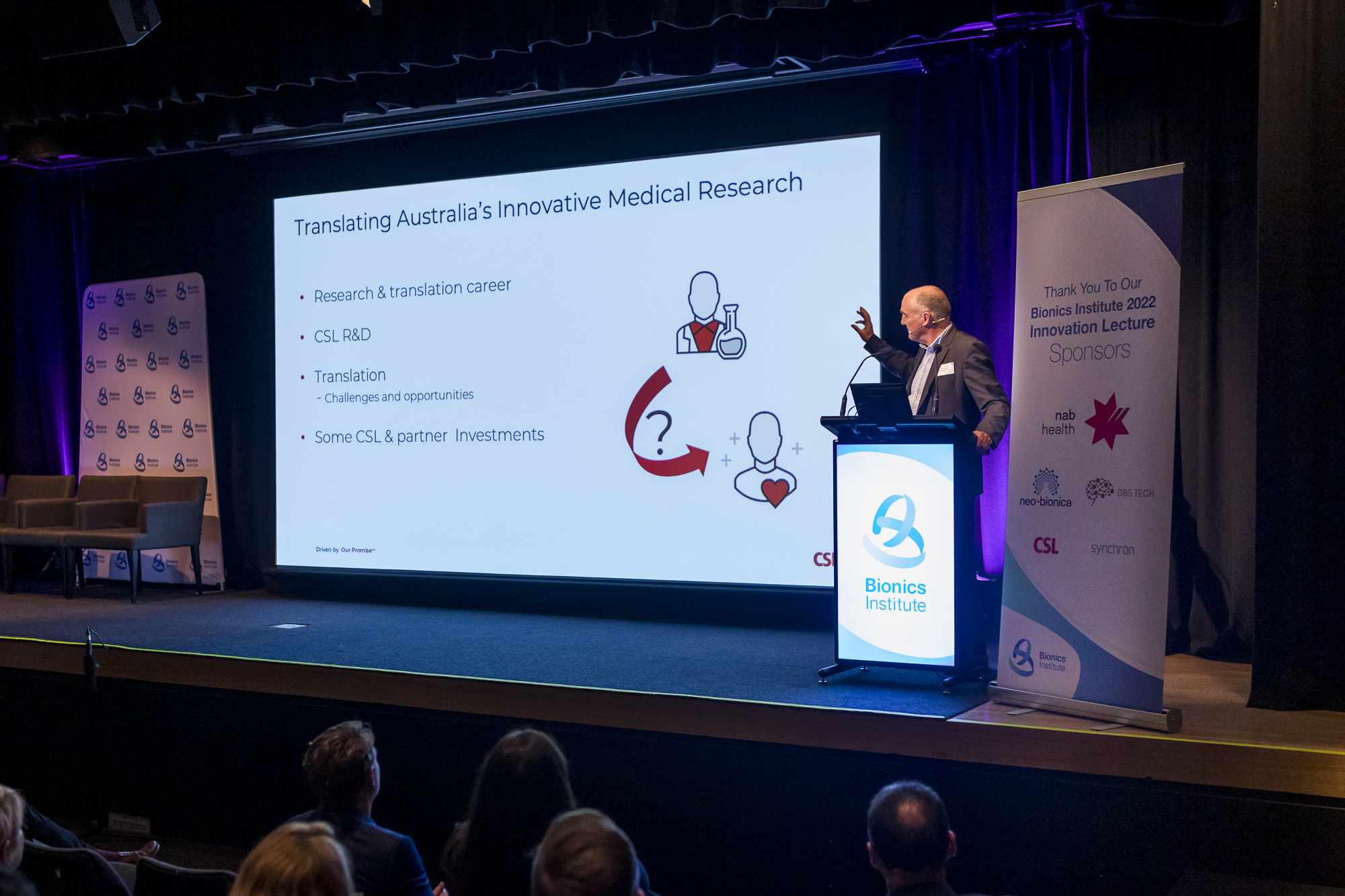

Dr Andrew Nash [00:08:59] . Thanks very much, Rob. It’s a fantastic opportunity to be here tonight to talk to this audience about innovation. From my perspective, it’s innovation in the medical research sector. It’s been a long journey for me from the times that I worked with Rob to where I’m at now at CSL. It’s been a very rewarding journey and I think it’s a it’s a career that really allows you to feel that you’re making a contribution to the health and wellbeing of Australians. But first, before I start, I too would like to acknowledge that we’re on the lens of the will Andrej people who are the traditional owners and acknowledge their elders past and present, and also acknowledge any other Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders that are here from other communities. So look, I’m putting together this talk for this evening. I was really thinking about, you know, the issues that as scientists and as employees within universities, within medical research institutes or indeed companies. The issues and challenges we have when we want to translate research. And I guess we would all agree that there has been an increasing focus on translation over the last few years. I think it’s interesting to note some of the change in language that’s occurred across that period of time. So when we talk about translating research, I suspect everybody here thinks about patients when we talk about commercializing research. I suspect people start thinking about investors and pharmaceutical companies. And I think it’s although it’s a false dichotomy, it’s something that’s led to a bit of a divide between the academic sector on one side and the commercial industry sector on on the other side. And I would say there’s been a huge effort over the last few years to really bridge that gap. And I think there’s some room to go, but we’re making some great strides. Salaries. You know, I think as as all of you will know, has been operating in Australia for over 100 years now. Our R&D is a global organization now, so I’ll talk a little bit about in a minute, but our research or at least early stage research is based here in Melbourne. We, we think Melbourne’s a fantastic location to undertake early stage research and to translate that research. So we have a real vested interest in the ecosystem. For us we see a thriving, you know, really substantial small company innovation sector as really critical to the success of CSL. So when we think about investing in the sector where we can help, you know, it’s not only that we want to see companies grow and develop, it’s that we understand that that’s critical to our success as well. There we go. So in terms of what I’m going to talk about today, I will, as Rob said, give you a brief background to my research and translation career and an introduction to CSL, R&D. And that’s more to give you some context to some of the comments I’m going to make later about where I see the opportunities for improving translation and then going on to talk about challenges and opportunities in the translation space and to talk about some of the things that CSL and our partners are undertaking in order to really facilitate that, that translation. I was looking at this icon and just this icon will come up later. And just in case anyone is wondering, that figure down the bottom is a patient. I’m not sure. But that’s that’s translation from science to patients. So when you see that coming up, that’s what I’m talking about.

Dr Andrew Nash [00:12:42] Now in terms. Of, you know, the areas of the you know, the drug development research, drug treatment that I’ve been in. It’s summarized briefly here. And I guess to start at the end, the one one thing that I’ve certainly learned from all of this is that having more money is certainly better than having less. And and the reason for that is not because if you have a lot of money, you have a lot of good ideas, because I’ve seen a lot of people spend a lot of money on really stupid ideas over many years. But what the what the finance and the support allows you to do is to really go out and look for those novel ideas. And when you find them, it gives you the resources to translate them. It’s we know it’s expensive to take a drug from, you know, research bench through clinical trials and resources and access to resources, really important. So in my career, I’ve gone from an academic in a research lab where if you managed to get a grant for a few hundred thousand dollars, you you’re down the street buying the bottle of champagne through to where I moved to the biotech sector in 1996. And that was a timely move. I think there was a, you know, the first phase of growth in the sector here. You know, the first real golden age for biotech probably was from the early nineties through to the mid 2000 and I was lucky enough to join. Right. And I see John Grace is here tonight too, is one of the first CEOs there. And that was a real opportunity for me to see how the sector worked. I’ll come in a little bit later on, on some of the some of the things that we did right at that time, but some of the things that probably weren’t working that well as well. And then, you know, in that environment, you know, we were spending around, you know, 10 to $15 million a year on research and we were a cash burning company, you know, going through about 5 million a year. We did add some revenues, but even that seemed like a lot of money at that time. And and then moving on to Zenith and the acquisition of of Zenith by CSL. When I arrived at CSL in 2006, 2007, we were spending about $161 million a year on R&D and the market cap of the company was about $5 billion. And so if you fast forward 15 years, you know, last year, financial year, 2021, we spent 1.2 billion on R&D and the revenue of the company was around $10.6 billion. So I say that not because, you know, I’m overwhelmed with the success of CSL, but because the growth of CSL has allowed people like me to really pursue our passion of translating research and making sure that innovations in Australia and elsewhere have that opportunity to find their way through to patients. Shareholders are important. We talk a lot about our shareholders at CSL, but I can guarantee you we talk a lot more about patients than we talk about shareholders. So this is what CSL, R&D looks like at the moment. There’s five therapeutic areas we work in, plus vaccines. The idea of a therapeutic area focus is relatively new to CSL, a big really a big strategic shift for us. For most of our life, we were a platform focused company. We had plasma. What drugs could we develop out of plasma in 2016, 2017, as the company was growing, we took the opportunity, become much more focused and started developing skills and capability in the therapeutic areas that you can see here. Obviously, some of these we’ve been involved with for many, many years. So immunology, hematology areas at CSL had always been strong within. And of course we’ve made influenza vaccines and other vaccines for a very long time as well. But areas like respiratory disease, transplant and cardiovascular are relatively new for us. We’ve always had a plasma fractionation platform. That’s what really holds the company together. I suspect, though, if you ask most people on the street, you know what to say, cell mate, they would tell you. They make flu vaccines and they wouldn’t know much more. Flu vaccines are a very important part of what we do but don’t represent sort of 20% of of our revenue overall. Most of our revenue comes from plasma products coming from plasma fractionation and recombinant DNA technology. And more recently we’ve invested in developing a cell and gene therapy therapy capability. And when you put all that together with without our commercial team, you know, we get the revenues we do. And on average we put sort of 10 to 11% of revenue back into R&D, which gives us about $1.2 billion to spend. That’s not high globally, but it’s, you know, a significant amount in the context of Australian R&D that gives us about two and a half thousand or so R&D staff at covering, you know, the very early stages of research which I laid all the way through product development, clinical development, regulatory phase and the whole variety of people that support that process. Now that’s, that’s, you know, at a high level what CSL looks like in terms of R&D. But I thought you might be interested before we start talking about the system in looking at some of or one of the new products that CSL has been working on and indeed a product that’s just recently finished its Phase three, give you a sense for the type of research we’re doing and the patient focus that we have. So this this patient here suffers from hereditary angioedema. It’s a it’s a genetic condition, affects sort of one in 10000 to 1 in 50,000 people. And it’s a pretty horrible condition. You can have spontaneous vascular leakage in a variety of locations. This person is having a cutaneous attack. If you have one of these attacks in the larynx or in the surrounding area, they can be fatal. It’s due to upregulated protein cascade leading to Brady carbon and production. You can see the pathway down here on the bottom right of the slide. The underlying mutation is in a, C is in C one inhibitor. And ultimately without C1 inhibitor, you get uncontrolled progression of that pathway through to Brady and which causes the swelling that you can see here. The attacks are unpredictable. People can tell there’s a sort of a surprise syndrome where they can tell those attacks are coming. But, you know, really there’s been little to do about it except sort of on demand treatment with replacement therapies targeting replacement of the C1 inhibitor and in fact, a therapy that was developed by C. So when we looked at this, these patients weren’t treated well. It was intravascular infusion. They weren’t treated prophylactically, though, treated when they were having an attack, and often it was too late. So we decided to try and look for new ways to treat these patients. Most of this work was done here in Melbourne, but with collaborations in various locations around the world. This is just some of the pre-clinical data that the scientists in the room will recognize this sort of work in their animal models of different diseases and we’re looking at the efficacy of our clinical development candidate. So on the on the left hand side there you can see really what is a model of vascular leakage or hereditary angioedema. The masses filled up with blue dye. You induce vascular leakage, the blue dye moves out into the air. And if you treat that mass with three of seven, which is a similar antibody, if not identical to Garrett, that’s MAB. You can block that that swelling. We also know that fact at 12 the target for Garrett Desmet is involved in the contact activated pathway of coagulation. And that’s what causes your blood to coagulate when it, for example, hits an oxygen either in an echo system or a filter in a bypass system. And patients get loaded up with heparin to stop that coagulation, and that causes bleeding problems. What we’re able to show is that if we treat patients with this antibody, we block to factor 12 activity, we can prevent coagulation from forming on the fibers of the oxygenate, as you can see there, in the same way that you get to the same efficacy as you get with heparin. The big advantage was if patients that are on heparin, you know, have any sort of disruption, physical disruption, they can bleed profusely. And it’s a terrible outcome. With this antibody, you can prevent the thrombosis, but you don’t get a bleeding effect. So that’s a really interesting opportunity as well. But what we’ve been doing, we’ve been pursuing the hereditary angioedema and this is the result of all of that work. This is a phase two study that we did over sort of 2021, 2022, published this year in Lancet, where you can see that patients went from having 4 to 5 attacks of hereditary angioedema per year, per sorry, per month to essentially having no attacks. So this was you know, this was a life changing therapy for this small group of patients in this Phase two study. I’m pleased to say we’ve now completed the Phase three study and the Phase three study. We met the primary and secondary endpoints. The drug was so safe and well-tolerated and we’re planning on filing this drug in the US next year. So a fantastic outcome for a team based in Melbourne accessing Melbourne technology, Melbourne capability, Melbourne manufacturing capability. The antibodies for this drug were manufactured at our Broadmeadows facility and you know, a whole lot of resource that is being developed by CSL with partners such as the State Government went into making this effective. Of course when drug companies have a drug that works in one area, they were always keen to find other areas where it will work. And just to finish up on this piece of the story, this is some really interesting work that we’ve been doing with scientists down at the Alfred Hospital. We we over the last several years have been working with the group there to build a biobank of samples from patients with pulmonary fibrosis. And we’ve been able to use that biobank to look at the role for factor 12 in those diseases. And this is an excellent example of some data that’s just been published now where we’ve been able to differentiate gene expression in the apex of the lung compared to the base of the lung and show it’s different in patients where disease is. Compared to where it’s not. And without going into the details, this this drug, Gardasil, MAB, is now in phase two studies for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis as well. So a great example of innovation by scientists at CSL in Melbourne working with a variety of collaborators to take local innovations through phase one, face to face three and hopefully on to the market, but also pursue other options for those drugs as well. So thats, if you like, a bit of context. That’s sort of my history in the biotech sector and some of the things we’re doing at CSL now. So I’d like to sort of step back and take a look at the the ecosystem, the biotech small company sector here in Australia and think about how it’s developed over the last 20 or 30 years or so. Now, I would say that that when when I first worked, started working in biotech back in the mid-nineties, the ecosystem was was far from optimal. So if you looked at the players that were involved, there was academic scientists, there was industry, large pharma, very small number of biotechs. They were the hospitals with the patients. And there was really a lack of connectivity between those groups. They did work together, and that was a good example of a company that worked extensively with the academic research groups. But the links to the hospital and the patients weren’t really there and there was a genuine lack of connectivity that I think stopped us from moving forward. And really what that did was it meant that there was a big delay in taking great ideas and great innovations and moving them through to the medicos and the treating the treating medicos and the patients. A long and winding road, if you like, to get to where you want to go. I guess it was also hampered by a lack of skills and understanding of how the industry worked that time. Dr Andrew Nash [00:24:53] Although I must say, I think. In retrospect and I’m not insulting anyone here, I think we were probably a little bit naive in understanding of how the whole system and the whole process worked. But sometimes a bit of naivety leads you to move forward in an unknowing but successful way. So if you look. Forward to so this is where we were and I think what I’m what I’m trying to show here is where I think we really want to get to in the future. And the question that I would pose to the people in this room is, where do you think we are on this journey now? You know, have we reached what I’ve called the future here or are there still pretty big gaps? And I guess I would argue that there are still quite big gaps, which I think we all need to think about and work on and try and build this type of ecosystem here. It’s about scientists coming together with industry and patients and trading physicians and investors and developing an ecosystem which can optimize the translation of our innovation. So we need our scientists to be properly funded. It is perfectly clear to me, and I presume many others in this room as well, that the decline in the the success of basic research grants, the decline in real terms in NHMRC funding, and I see funding is really damaging the future of Australian innovation. There’s no question that in my mind great medicine comes from great science and if we don’t have the great science and we don’t support that, that is ultimately going to really damage out our opportunity. So we do have things like the MRF and I think the governments are really putting in a big effort towards translation. But we need to continue to focus on the the early stage activities as well. If you look, you know, we need I’m going to talk a little bit about incubator facilities, industry co-location, that sort of thing. We need to encourage investment in onshore R&D and advanced manufacturing. We need to enhance translational research and medicine, and we need to support precincts. When I put this diagram together and you look in that piece in the center, which is where all the pieces of the puzzle overlap, and ask yourself, what is that? That is a medical research precinct. That is what you find in Parkville. That is what you find in Boston. That is what you find in Cambridge. That’s the space where physicians work closely with scientists, with investors in the next room thinking about how we can capitalize on these innovations. So we have these great precincts. We just need to develop them further and make sure we can optimize the outcomes.

Dr Andrew Nash [00:27:27] The piece between the scientist and industry there. I put a red dot because that’s where I think an incubator exists as well. I’m going to talk a little bit about the CSO incubator shortly, but I think that’s really important in terms of bridging that gap between industry and basic research and science. And I think if we can get that right, then the road to a successful outcome, the road to new medicines for patients in really serious need is much shorter than it was. I did have a straight road there, but I took that away and put that line there because it’s never going to be a straight road. Drug development is hard. It takes a long time. It’s expensive, it’s highly competitive. But I think if we invest right, we can really make some great strides. So I just wanted to look at, you know, that process of innovation in a sort of more linear way. And, you know, think about how you do get from the medical research piece through to the product, the things that happen in between, and ask the question about where, where the gaps are, you know, what we need to invest in to fill those gaps. So I think we’re all pretty used to this this sort of pathway. Right at the start, of course, we had a government funded medical research. And at the moment there’s quite a lot of funding, I would say, going into assisting those scientists develop what I would call investable opportunities, bringing their research to a point where a visa or a company will partner and invest with them. And you see a lot of funds like Pre-Seed Proof of concept get by to build funds. At the moment, AMREF Via Curator is supporting such a fund, and just a few weeks ago at the University of Melbourne, we high announced their own early stage funds and indeed its itself. We have an accelerator fund that I’ll talk about. Those assets either end up in startup ventures or they’re licensed to Big Pharma. Often if they are in a startup venture, you end up with a partnership and you know, you’re looking for for for the product in then there as well. I think both pathways both pathways have risks. And I would say that I’ve experienced firsthand those risks on a number of occasions. So when you’re a small company partnering with a large pharma, you know, looks like a fantastic opportunity. Until there’s a change in personnel there, they prioritize your portfolio and you find dry pea handed back and you’ve lost ten years or five, 5 to 10 years off the development time. That’s that can be a real challenge. Doesn’t happen all the time, but I would say it happens more often. Then you get a successful outcome. Of course, the other opportunity or the other pathways to try and push all the way through with a startup venture, and we see some examples of that in Australia at the moment. Robyn, I was talking about up there a little earlier where what is essentially a small startup company is pushing into phase three, you know, at great expense. And of course the challenge there is, you know, the risk of a lack of skills and resources to get you there ultimately. So these are the challenges. You know, if you think of it in a functional sense, as a scientist like I do, what does all that mean? What is translation of innovation look like? From my sense in the perspective of CSL, these are really some of the key steps that we takes. On the left. You have your basic biomedical research through the steps of pre-clinical validation, lead optimization, translational science, etc., etc., ultimately through into the clinic. And to support that progress through the clinic, you need to have great translational medicine capability. You need to have great manufacturing product development capability. This process relies on, you know, activities that are highly regulated. So you need a GMP manufacturing facility, you need access to GLP toxicology. And if you put all those things together, you can get through phase two by three and end up with a translated product. And down the bottom there on the right hand side, it, for example, is a factor that we developed to treat hemophilia B patients several years ago now, but which has been a revolution in the treatment of those patients and and now is the number one therapy to treat those people that is available. So that’s that’s really the the pathways that are there when you think about them in a linear sense. So what, what what are some of the gaps that I see when I look across those pathways and and how can we close those gaps? And, you know, what I’ve chosen to do is give you some examples of how CSL is working with our partners to try and close some of these gaps. But I fully understand there’s probably many people in this room that have the same, you know, long term view of where the sector can get to and are thinking about the same issues in this in a similar or different way from, from what we are in investing to try and take us forward in this space as well. So, you know, as I indicated earlier, clearly, clearly, the more investment we can get, the better off we’ll be. And that needs to be support for both basic research and translational research. And one of the things I think we really need to work to do is to bridge that gap between industry scientists and academic scientists. I, after all of these, is I’m still amazed at the lack of understanding among some of my academic colleagues of what the drug discovery process looks like and and sometimes their disdain for the science that goes on within an industry setting. And speaking as someone who’s worked on both sides, I can tell you that the the quality is as high, if not higher on the industry side, because it has to be, you know, we’re not putting drugs into mice. We’re putting drugs into humans. And if those drugs don’t work and have adverse. Quinces. You know, that’s not a good thing for us. But encouraging and understanding from both sides, I think is really important. We need as much peace in accelerated investment we can and we need direct industry investments in start ups as well. We need more investable opportunities. You know, I say and I suspect others see here, you know, opportunities that are brought to us that are really underdeveloped and that underdevelopment is because of general lack of understanding of what it takes to get to that next step. So I think there’s a real role for industry and other people in this room to go back into the academic sector to to talk to the people that are the innovators and help guide them along that pathway to to help them understand where they need to get to, to have what we would think of as an investable opportunity. And there’s a couple of activities that we’ve got going on in that space. I won’t talk about it later. But one thing is that we’ve recently done we’ve recently taken out our biologics library and set up a center for biologic therapy discovery in we high that that’s just for the partners of the moment but hopefully at some stage that center will become more widely available for for groups around Australia. We need to really focus on developing the innovation ecosystem that includes people, skills, infrastructure and technology. And we need to look at building Jake’s capabilities as well. Just keeping my eye on the time so I’ll move forward. So in terms of some of the things that that we’ve been doing and I know and which I think are important to do and others are doing as well, I’ll take you through some of those now. So we’re certainly investing more of our R&D dollar in the early, early innovation stage. We’re doing it both here in Australia as one of the five partners involved in the brand and by catalyst funds. So I think those funds are, you know, totaling seven or $800 million and CSL has about 60 or $70 million in there. And we see that as an opportunity not only for us to see the pipeline of opportunities that are coming through from the brand and group of organizations, but also to put our money where our mouth is and invest in these small companies. We also have partnerships with startups at Stanford, the Science Center in Philadelphia and based launch and by Apollo in Switzerland as well, just as an example of how companies can partner with others to invest in small startups. We’ve been working with the University of Melbourne for many years on the vaccine for periodontal disease, a really nasty condition that’s poorly treated at the moment. Ultimately, that technology didn’t work for us. It didn’t fit within our, you know, our focus areas. But we thought the the pre-clinical data certainly was strong enough to warrant someone testing it in the clinic. So together with the University of Melbourne and Brandon, we set up the enteric and did enteric as well on its way, despite issues with the pandemic of getting its vaccine candidate into patients next year sometime. So we think that’s an example of how companies like us can invest in the local biotech sector. One of the things that we do do as well as we look for really early stage opportunities in medical research institutes. And we fund those opportunities and we give the people that are working on them access to our scientists and our advice. And we think that that will help us create more investable opportunities. So these are two year funding packages that pretty asset stage novel targets therapeutics. They can be in a range of different areas and as I said, a focus on engagement with CSL scientists. So what we see this doing is really creating a pool of opportunities that we can move into our own portfolio at some time in the future. But equally, if we if we do create value and it’s ultimately not within our therapeutic areas of interest, we’re very happy to see these developments partnered and commercialized translated by others. So this has been a really successful program for us, which started in Australia, moved to Central Europe, in the US and in the last round. Eight out of our ten successful applications came from France, which I think was a pretty interesting situation for us to find ourselves in terms of, you know contributing to the development of skills and infrastructure and technology. We made the decision about, you know, 15 years ago and actually someone was telling me this 15 years to the day to move. Our research group says some research group into the park precinct. You know, we’re only six kilometers away, maybe less behind the zoo in Parkville. But that was a huge gap, as it turned out. And if you want to engage, if you want to reap the benefits of a high quality medical research precinct, you have to be there yet, be right in that space. So we moved our group down to to the building. You can see here, which is on the by 21 campus of the University of Melbourne, we have about 4000 square meters there. We have 100 and 5060 scientists there. They’re doing all types of research that contribute to the discovery and development of drugs. And we have multiple collaborations with with institutes in the precinct, hospitals in the precinct and others around Australia. You know, and our one learning from this is that precincts, the ability to walk out the door and talk to a physician scientist who’s treating the patient that you’re developing a drug for just has enormous advantages. And so we’ve doubled down on on on this site. And, you know, we’ve doubled our size, actually, since where we’ve been there. But not only actually have we doubled down on having our research within the precinct, the success of of the group there and the value of being co-located has really driven us to take the decision to ultimately close down our site in Poplar Road and move all of the company headquarters, all of our executive, a lot of our product development people, our commercial group up to the top of Elizabeth Street to really be in the heart of the precinct where we can engage. So to to, you know, this project’s been going on for a while. And actually, there’s as we speak here, there is the illumination event where the big the sale sign at the top is being turned on. I’m happy to be here. So so that’s a real milestone for the project. But one of the things when we looked at that building, we thought to ourselves, what can we do in this building to really benefit the biotech sector and the local start up community? And at that point, we engaged with the with we high in the University of Melbourne and we came up with the concept of a partnership to develop a biotech incubator. And lo and behold, a few years later we have a $95 million project which will be located across two floors of this new building. It will be an incubator run by an independent operator, not by one of the partners. It’ll have space for up to 40 startup companies. And the launch date we’re targeting 2024. We’re hoping it’s early in that hopefully like 2023. MAHTANI Thank you. But I think it’s a really it’s a really exciting initiative. We’ve had fantastic support from the state government. So of that $95 million, 25 million came from Breakthrough Victoria. I think the State Government and Breakthrough Victoria who are investing in startups themselves, understand the value of having a capability there to really support those companies. So we’re making a lot of progress. We were doing a tour of the building there the other day and as I said, the lights are going on. When I look at the incubator, we think it has all the key ingredients to make it successful. Ahead of this program, we we looked at all of the incubator clusters around the world, all of the academic, you know, the really strong academic translational sites, and looked at what it was that were making those successful. And, you know, asked ourselves, Will, can we meet those criteria here? Can we offer that same capability at a site in Parkland? And you can say that every every one of those boxes is ticked. So we think it’s fantastic for small companies to be co-located with large companies. We think it’s great that they have access to affordable wet lab space and support services, facilitated introduction to investors, mentoring, proximity to the CBD, all of those things that can really help a little startup make the transition. We are doing this because we believe in the ecosystem, we believe in the precinct. We don’t see how these companies don’t have to be in our therapeutic areas of interest. They just have to be based on really high quality science and they have a strong investment base. But there’s been a lot of interest and I think we’re very comfortable that this will be a thriving incubator within a relatively short space of time. So just just to finish up, you know, I think one of the things that we’ve learned over the years at CSL is that if you’re not doing open innovation, if you’re not reaching out and engaging with the broader medical research community, then ultimately you won’t be competitive and you will fail. So we’ve really made a big effort over the last several years to develop an external innovation strategy, and that’s been led by modern brain, who is who has done a fantastic job and the pillars of that strategy that you can see here. But for us, it’s all about engagement. It’s about developing the ecosystem, building skills, all of the things that that you need to really be successful in translation. So I guess just just to finish up, I’d say I think there’s been a lot of progress over the last 30 years. I think we’ve learned a lot, and I think those learnings now are really starting to impact the way that we’re doing things. I think there’s a lot of people here now who have a lot more experience, who have who really understand the drug development process. I think we’re at a point in time where the investors are there and the dollars are there, although that does tend to go up and down a little bit. But I guess I’m really hopeful about the future for the small biotech sector and the future for, you know, our ability to translate medical research for the benefit of the patients that we want to treat. So with that up, thank you for your time. Did you want me to answer?

Robert Klupacs [00:43:32] Because I may never. So thank you for a fantastic speech, Andrew. You’ve improved a lot since I first saw you speaking 30 years ago. And we are running short on time, believe it or not, because you are loquacious. But I have got one one question that I can ask, and we have time over drinks and also in the panel session later to ask you some questions. But there was one that came through that I like to ask you. It’s from someone in the audience, Andrew. What have you learned from Cecil’s global collaborators that Australia could emulate to improve translation of research?

Dr Andrew Nash [00:44:07] I think one of the things that is really obvious is the extent to which institute academic groups internationally, embrace entrepreneurship and and I guess innovation. So if you look at the US and increasingly in Europe, there’s such a focus on, on, you know, innovation, on translation, on entrepreneurship that, you know, when we think about how we partner in the U.S., we have to we have to think about it in a different way because the environment is so different. So what I would say is the lesson from overseas is that, you know, one of the things that’s critical if you want the ecosystem to develop is that you have to develop the right mentality and the mindset within our fantastic universities and research institutes.

Robert Klupacs [00:44:54] Fantastic. Thank you. Thank you for a great talk. As I said, we will have time hopefully at the end of this and definitely over drinks to talk to Angie more. And that last answer to the question is a great Segway to the speaker. That’s coming up. I know that many of you in the audience because we track you have downloaded the new Bionics Institute podcast Med Tech Talks, where I interviewed some leaders in the field about their journeys. Two themes have consistently come from those discussions. One, how hard it is to attract funding for early stage research, and two, the lack of people who are willing to take risks on early concepts. Fortunately, we heard from Andrew that that may not be the future, but the people we’ve spoken to, that’s their reality. Our next speaker is very familiar with this scenario. Associate Professor Tom Oxley study medicine at Monash University, specialized in interventional neurology and completed the annual engineering at the University of Melbourne. He’s the co-founder and CEO of Synchronic, a company set up to develop the stench road and implantable medical device that can provide thought controlled actions to people who are paralyzed or have severely restricted movement. To put it into some context, I know many of you in the audience have heard all about Elon Musk and Neuralink and what he’s going to do for the world. The state trade is well ahead of Neuralink and is currently in clinical trials. This is strange. Developed technology leads the world in the emerging area of brain computer interface. Unfortunately, Tom was unable to join us in person from his home in New York, but has been more than kind to make a presentation via video. Notwithstanding that his colleague, Dr. Nick Opie, CTO and co-founder of Sing John, is here tonight and can answer one or two audience questions after the video or for running over time after drinks tonight. I now like to hand over to Professor Tom Oxley.

A/Prof Tom Oxley [00:47:08]. Tom Oxley here from Synchrony in New York City, very excited to be here and chat for a few minutes about our brain computer interface technology and give it a little bit of a sneak peek on the ten year journey from University of Melbourne spin out to now small growing corporation. So synchronic, I just want to take you through the vision and the product and what we’re building. Really, the vision of our company is to decode the brain. The way that we’re going to do that is by reaching all corners of the brain, using the brain’s natural highways, the the blood vessels. But our goal, our ultimate vision, is to build a hands free computing personal computing platform, which I think is an inevitable movement in society, away from handheld devices to having darkly brain controlled devices. Why is this important? Because there are 100 million people in the world who can’t use handheld devices like you or I, who are in desperate need of some form of control of technology that does not depend on their bodies. So here’s the concept. The concept is that people who live with paralysis are unable to control their body, like you or I. There’s a range of conditions that cause this. The most common is stroke, but also motor neuron disease, spinal cord injury and other more common things like rheumatoid arthritis that stop our ability to use our hands effectively. So the concept is that we go into the brain through a blood vessel. We get to the part of the brain called the motor cortex. We deploy the device in there, can record local brain activity, and then it converts that into a USB Bluetooth signal that comes out of the brain and is able to control digital devices. This is what this tension head looks like. Self expanding night in Austin with a sensor array. We had to completely re overhaul how manufacturing of stents is conducted because we had to have two layers of metal and required an insulation layer. So essentially we had to come up with a mechanism of 3D printing multiple metal components into a stent which had not been done before. This was the final result. We’ve called it The Road and it has both not no insulation layer and platinum sensors on the scaffold. And we have we’re figuring out how to deliver these safely into the brain. Put it all together. You have a self expanding device next to the brain area called the motor cortex, which is the part of the command center that controls our muscles and our body. It comes out of the brain through an actual hole, which is a blood vessel out of the holes in the base of the skull. And then that plugs into a device in the chest that sends out the information wirelessly through Bluetooth. This was our first patient. So this is an angiogram that shows the blood vessels spinning around in the brain. And you can see if you look closely there, the device outline coming out of the brain and that largest blood vessel in the brain called the superior sagittal sinus. Once it’s in place, we then declare or classify the types of brain signals in the brain that are related to certain types of movements, and they’re distributed in different regions. One bits of your hand, one bits of your shoulder, one bits of your foot, etc.. So we are essentially building a dictionary of the brain to decode different types of movements from the brain. And once we can classify that, it doesn’t actually matter what your brain was connected to before, because we’re bringing out data wirelessly and you can then use those classified types of movements to control external devices. We turn this part of the brain into a joystick, essentially. So we’ve been working. We started as a research group, and one of the initial problems was what does the brain signal look like when you record it from the blood vessel? It looks very similar to a surface array that’s implanted through open brain surgery. But there are some differences here. And so we’re in a very fortunate position now of patenting and making proprietary the types of classifications of brain data that we see in a way that can be converted into digital device control. So here’s an example of one of our patients. You can see his hands are not moving. We’re converting those classified types of brain activity into outputs that enable him controlling a keyboard. And he this is a man with motor neuron disease who just sends a message to his wife to let her know that he’s in need of something. And so she then gets the buzz from the phone. So previously, where patients would have motor neuron disease, for example, they completely depend on their caregivers or partners to come and try and interpret what it is they’re trying to say, giving them access to messaging, something that you and I take absolutely for granted. It really incredibly opens up your capacity to be independent in the world again. So we’re trying to give back the power of digital technology to people who don’t have the mechanisms of normal use of those devices, which is the hand. Okay, this is a journey along the way. Since 2011, when we wrote the first patent, Nick Opie and I, the co-founders of the company, and all the way through to 2023, we’re heading towards a pivotal study. This is probably a bit scary in terms of how long it takes to bring a medical device all the way through to market. And we’re still not there yet. We’ve still got a long way to go. But these early years, which I’m going to talk about a little bit, you know, from 2011 through to 2015 were benchtop fabrication, animal studies really hard, hard at medical research and science to be done. Before we knew that we had a product that needed to then move into a commercial or more development type stage. That happened with the series, a round of financing, which I had a lot of trouble doing in Australia. I actually came to the US to do a medical fellowship in this neurosurgical procedure and it was when I got to New York I met, I met investors who are willing to take the risk and we didn’t quite have that risk appetite in Australia at that point. And then so we spent that 3 million on the series A to get beyond the animal stage into the first in human stage. And then about 18 months ago we raised a total $50 million Series B round of financing, which is now carrying us into the next stage, which is moving towards the later clinical pivotal trial stage, discussions with FDA, discussions with Medicare, figuring out reimbursement, the business model, and getting ready for commercial launch the team. Has stayed small for a very long time until the series B financing, where we’ve jumped from nine people to 55 people. And half of the team is here in Brooklyn and half the team is in Melbourne. So I’m going to talk a little bit about product development, just to give a little bit of a window into those early years about some of the challenges. This was us in the in the Howard Florey Laboratories, just opposite Royal Melbourne Hospital in the Parkville precinct. This is Nick and I in the angiography machine and Steve and Gil are there as well. We were doing a lot of sheep work trying to demonstrate that this device could be put into the brain through the blood vessels, that it was safe, that it worked, and we didn’t have the benefit of advanced manufacturing techniques. I mean, Nick was essentially making these devices by hand in our lab in the Department of Medicine and University of Melbourne. And just to give a sense of where we came from, we were taking off the shelf products that were basically in the rubbish bin, cleaning them, repurposing them, fabricating them by hand until we eventually figured out how to do this in a good manufacturing practice technique that was suitable for human use. It was a hard slog. We were basically one of the issues we had was the sheep’s heads weren’t big enough to get into the blood vessels, so we would be going out to the farmers, finding the sheep and pointing out the sheep that had the biggest heads and then driving them back ourselves from the farm. This was what it took to make things happen. This is just an analogy of the sort of things that you have to do to make things happen early, early in the stage of development. Eventually, we pieced enough together to have a really impactful publication in a high quality journal. And then from there on, that’s what was formed the basis for the series, a round of financing. So, you know, advice around patenting. This was our first patent. I just wanted to make the point that you have to be aggressive with patenting. You have to get second opinions. You’re probably existing within an institution. The institution doesn’t always know what you need. Get second advice, get external advice and patent aggressively. Yeah. So, you know, just to quickly make the point, going from academic clinician to commercial hats is very challenging and there are lots of different pressures coming. And I think the environment is going in a really positive direction. In Australia there’s more support for entrepreneurial attitudes, but sometimes you come up against headwinds and they’re challenging. So, you know, I would advise everyone that you have to go out there, negotiate aggressively for what you’re trying to do and always get second opinions. Just to make the point that, you know, publishing is really important. If you’re doing a deeply technical, sometimes you don’t want to publish, sometimes you want to be in full stealth. Sometimes you want to show the world what you’re doing to attract investment and attract people to recruit. And that was very important for us. And I think one of the things that’s really for me was time and time again, making pitches to investors is very challenging. You keep getting told by very, very smart people that what you’re doing will not work for really good reasons, and often for three or four really good reasons. Times 200. And you have to have a belief that you’re doing something that you think is worthwhile, that you think is going to work, and you’ve got to find a way to keep going forward. Things happen along the way. You have to be ready to be responsive. After our nature biotech paper came out, it was picked up by President Barack Obama in a completely unexpected event, and suddenly that led to a range of interest from investors. And we had to jump on that straightaway. So you never know quite when things are going to come your way and you have to be ready to ride the waves that are coming. And after those 200 knows, it just takes one investor to say yes. And this is Martin Dake who led this series. A round from Neurotechnology Investors has now become chairman of our board and a very close mentor of mine. It just takes one person who believes in what you’re doing and then all the other doubters will disappear into the background. Just to finish up. So we landed a series B, we were not in stealth mode. We had a very active idea of going out there and making as much noise as we can. That’s actually how the Series B happened. We got into the Wall Street Journal. We were telling our story and the investors came to us. And so all the doors that I’d knocked on had said, no. When people come to you, it just seems to be a different psychology. That was the experience for us. So I think I’m running out of time. I don’t want I think this is just the start of your conference, so I’m going to try and finish this up. But building a culture of excellence has been a real challenge and a joy. And so we’ve gone from a very small team to now hitting about 55 people, an incredible journey. I would say mentorship is one of the most important aspects of growth and in leadership, and especially when you’re walking around blind corners, you know, the one that really springs to mind is actually not there. But it is it is the CEO of a company called Saluda, John Parker, who gave me really good advice early on about how to negotiate the license terms. So you’re facing things you don’t know how to do. Go and ask people who’ve done it before. Even if you get 5 minutes of their time, it can be lifelong advice that you can then grab on to finally, you know, the journey from the lab to then learning how to do storytelling and then presenting. It’s been an interesting journey. A really critical part of raising capital is the storytelling and being able to present. That’s been a big that’s been a big joy of what’s of last few years. Just to finish with you guys, the three things that I wish I knew when I was getting started, number one was the basics of negotiation. It’s really simple. Always have a walk away. Never enter a negotiation where you don’t know what you walk away is. Otherwise they’ll squeeze you for a really bad deal and you’re going to be miserable. Number two, I mentioned earlier always get external advice. This is especially true for when you’re looking at doing patents and then finally you have to be able to pitch off and you have to be able to be told that you’re wrong. You have to be able to embrace criticism and get back up and keep going. So thanks for having me here and good luck, everyone, with what endeavors you’re chasing. And I wish everyone the best and I look forward to being back in Australia soon. Thank you.

Robert Klupacs [01:00:00] Well, that was a fantastic talk. Nick, can you come up? Nick Opie, co-founder of Synchronic, it’s about five questions here. We’ve got time for one, but there’s a commonality. Lets you stand there and answer the question. The first question I got here three times is when is this going to be approved for human use?

Dr Nick Opie [01:00:19] Yeah, the question we always get right, hopefully in the next five years. So we’ve started and completed our first human trial in Australia. There were four patients that went for a year starting in 2019. All of the patients were able to control digital technology with one of these devices just using naturally occurring thoughts, there were no serious adverse events. The trial was a huge success. From the back of that, that’s where we got sort of FDA approval to then move into the US and start a trial over there while we’re continuing doing trials in Australia and, you know, expanding the sites to Queensland, New South Wales as well as Victoria medical devices. Maybe now it’s a long process, so we have to do this initial trial, then the pivotal trial and once that’s all, all gone to plan and then we get the approval to, to sell it in, in the US and then sort of Australia in the TGA will closely follow. So please be patient. We’re working as fast as we can and hopefully we’ll get out very soon.

Robert Klupacs [01:01:18] One last question for us to sit down, of course, or to actually. One is, why are you better than Neuralink? And secondly, how much will it take to get your product to the market?

Dr Nick Opie [01:01:29] How much time? Energy effort costs dollars? Yeah. That’s an interesting one. You know more than we’d like, but probably not as much as it should be. So we’re we’re pretty efficient and good with that coin. You know, we’re Australia. Australian, we can be came from making things on a shoestring. We’re pretty good at figuring out how to how to get the most out of our budgets. So a lot and we have to raise and we’ve had to keep raising and that’s why we’ve done done more of them. We think with the funding we’ve got plus a little bit more in the in the next round than we should be able to get to to pivotal where where we can start being, you know, revenue positive and start making some money off the devices and which will then obviously fund the other research. And your initial question why we beat the Neuralink? I mean, I think I think everyone who’s in this space, whether it’s brain machine faces or cochlear implants or whatever needs to be, you know, take that head off with them. You’re doing amazing work. I think there’s a lot of patients that need help and there’s many different solutions for them. So I think neuralink, you know, it’s just a different way of addressing the same problem. And I, I wish them all the best and they’re not us and not Australian.

Robert Klupacs [01:02:42] Thank you for that very diplomatic answer. You. I now like to ask the panelists to join me on the stage. Firstly, Andrew, if you can come up, maybe come up beside and sit on the seats over there. I’d like to introduce Professor Michel McIntosh, director of the Medicines Manufacturing Innovation Center and theme leader at the Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, otherwise known as MIPS. Professor Macintosh is an award winning scientist known for her inhaled oxytocin research, which promises to transform maternal health care, particularly in developing countries where price injecting capabilities and cold storage facilities present barriers to safe and effective childbirth. Welcome, Michel. I’d like to welcome Dr. Megan O’Connor, managing director of Kantara Consulting, who recently wrote a seminal piece published by Innovation Australia, about how grant funding in Australia needs to change to translate our world class research into commercial outcomes. Kantarais a biotech focused consultancy that brings top tier government relations and project funding services to the Australian SMB biotech community. Welcome, Megan. And last but certainly not least, please welcome George Kennelly, co-founder and chief operating officer of Sia Medical, a company creating technology to revolutionize the diagnosis and management of neurological conditions with a focus on epilepsy. Earlier this year, she was named Startup of the Year by the Governor of Victoria and recognized as one of Australia’s fastest growing technology businesses in the Deloitte Technology Fast 50 list. Welcome, George. Walk. Michelle, Megan, Andrew. George. I’m going to start by asking you the first question, Michelle. However, before I start, if anyone wants to ask a question of the panel at the end, please send it through Slido. You see that up on the screen? You can take a picture with your phone and send the questions through. I’ll get them on the iPad and I can pass them on to the people at the end. So starting with the initial. Michelle. We recently have a fabulous phone conversation on the on the podcast. And in it you raise the issue of how difficult it was to source initial funding. I wanted to ask you briefly to take us through the funding journey that you had. The lucky break that you referred to in the call and how that sounds led to accelerating your research.

A/Prof Michelle McIntosh [01:05:40] Yeah, great. Thanks. So this is all related to the the research that I’ve been working on for probably the last 14 years or so, and the oxytocin and making an inhaled product of oxytocin that specifically targeting low resource settings. And so the project funding started off with a $19,000 grant from a small group of I was the trustees, perpetual trustees at the time. And that $19,000 is probably one of the most important pieces of funding that we had because we just had nothing to do work at that stage. And soon after that, we were fortunate to. And it’s interesting how many parallels there are in the conversations. I was told not to apply for funding to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation because the idea was far too boring. And they fund blue sky ideas, but they did fund this for $100,000. And that allowed us to keep going. And then we were successful in getting the next round of funding, which was $1,000,000. And that meant I could hire a project manager, which was really important to be able to keep that going on in our academic. So I teach as well as do research. There was a strategic change in direction, so that happens with your philanthropic funders as well as commercial partners. Sometimes there’s just a change in direction and they decided they were no longer investing in development of new products in maternal health. And we went through a difficult stage. We found a couple more smaller grants, but a very challenging stage. And the the lucky break for us was that the the gentleman who owned the building that I do research in in Parkville came to visit and he is flavor of the month at the moment is Canadian philanthropists not the same particular philanthropist but he owns the building and he was visiting the dean of our faculty at the time and he heard about the project and he and his wife had a foundation that focused on maternal health, education and climate change. And the fact that we were combining maternal health with education really sparked his interest, but being close to tax time. So he just wrote a check there. And then literally that day there was no ask. He just wrote a check for like $100,000 and said, here, this will get started. But then he also subsequently went on to fund this for three and a half million dollars, which was matched funding. He said it was contingent on us finding matched funding and that is a great way to be able to leverage funding through other programs. So I no conscious of time and I’ve been asked to keep keep responses brief, but we have since gone through two phase to be clinical trials, raised over $35 million to date for the development of the program. It’s still within the university at this stage and we probably have another 30 million or so to raise to hopefully get a product to market.

Robert Klupacs [01:09:07] Fantastic. Megan, your recent article certainly resonated with me, and I understand many people across the country. It highlighted some examples of countries around the world that have gotten the government funding models right. Can you expand on what you think Australia could adopt from those models?

Dr Megan O’Connor [01:09:30] Yes. So, you know, the the commercialization pathway in medical research is very long and very complicated and risky. So I think getting the funding mix right is incredibly important. And that also not only includes funding universities, but also industry and supporting industry along that process, industry participants that are taking that long, risky pathway. So some models that are highlighted and some of some countries that I highlighted that do have very strong industry programs was the the SB R I program. The U.S. started this program and this is a small business research incentive program where the government essentially acts as a buyer and offers research contracts to industry, small business participants to undertake research and more applied research that the government, the the the community needs. And I think the government and since the UK has also adopted that model in 2001, and from that today the UK within Europe, 30% of biotechs reside in the UK. And, you know, part of that is part of this policy setting where in where where industry players are supported. And I think obviously government can play a very significant role in being a buyer in any industry, but particularly it does serve a place in the medical space, the health space, which, you know, a lot of which the government plays in as as the customer. Another example closer to home is Singapore. And Singapore has really just grown their industry from nothing to a real world player within 20 years, which in the scheme of things in general, particularly this industry is not a is a short amount of time. So they announced the, you know, directive, their policy agenda to to create a biotech industry in 2000. And the first kind of initiatives were to attract international foreign investment, both companies and also researchers to Singapore, to create that that that that system and grow that strong industry sector. And then they built infrastructure, significant infrastructure, which made it very quick and relatively cheap in this in the scheme of things, for companies to come and set up and start manufacturing quite quickly. And then they’ve also had significant research commercialization programs as well. And so today, some of you may know that Singapore, eight out of the ten top pharmaceutical companies have facilities in Singapore, and four of the top ten drugs in terms of revenue generating are manufactured in Singapore. So that’s an example of how government can play a massive role. And I’ll just comment on the local front. If, you know, if in the policy setting, if we really, you know, we want to grow and support the industry here in Australia, we have to remember that particularly in this industry, it’s a global market. So any policy settings that we have here have to be globally competitive and they also have to be stable because businesses in general, if you’re making innovate, if you want to attract businesses from overseas to set up significant facilities and business operations here, they need to have that confidence. The settings are going to be there for a while. And also, if you want to keep our companies here and not let them go overseas, we need that competitive setting on a global scale.

Robert Klupacs [01:13:47] Fantastic. Thank you. In your turn, George. So you co-founded Senior Medical with Dr. Dave Freestone and Professor Mark Cook in 2017. The company has been for some of you in the audience now incredibly successful. You’re now generating significant revenues. You have over 200 staff and have recently set up operations in the US and the UK. How did you overcome the barriers of funding and growth in the early days of your business? And can you tell us what the challenges you face now?

Dr George Kenley [01:14:25] All right, Ken. So in the early days, we were very fortunate to have a focus on early investment through the usual friends, families in Falls Avenue. That really set us up with it. We found like minded people who had a belief in what we were trying to do and how we were trying to get it. But it also kind of created and fostered an environment whereby we could make mistakes, and it was a welcoming environment whereby we weren’t going to be drawn across the coals just for that to happen, because that isn’t inevitably going to happen when you’re trying to find your feet commercially in these environments. So finding that kind of community who we could both leverage off in regards to mentoring, but also who we could test ideas against and inevitably have faith in us when we did inevitably have mistakes. But one thing that we were also very fortunate in, and it’s something that I wasn’t aware at the time. I don’t come from a medical or a health or research background, but we were able to achieve reimbursement for the services that we provide within six months of actually speeding up operation. So from the investment that we had so early on, we were able to make that actually last a hell of a lot longer because we could back it off with our investment with reimbursement that we were able to achieve in market so that we could stay the course. We could concentrate on what our core business was and what we were trying to achieve rather than being distracted or we still were, because we still had to go out to investment at points of time. But. The the effort and the concentration and the distraction that going out to raise capital can be. And it’s not your call. Your call. Our core business is to help people with epilepsy. Our core business is not to raise funds, but it’s inevitable that you have to do that. So being able to maximize the funds that we had reduced, the number of investment rounds that we’ve needed to undertake, really meant that we could kind of get our footing, get a grounding and really solidify our business in Australia. We then have been able to leverage just recently a large investment through Breakthrough Victoria, which has been pivotal in us eventually now finally being able to expand our business internationally. So we’ve recently spun up an office in the UK earlier this year and will be entering into the US market at the end of this year as well. So that has meant that our challenges have changed from early days when we were bootstrapping existing hardware and getting reimbursement in the Australian market. So now where we’re challenging in with global supply chain manufacturing at scale, being able to understand the US health insurance landscape and how we actually enter the market and the UK market, how do you enter? That is very different from Australia. So the fun challenges that we’re up against, but it’s really about growth and our ability to scale to meet that demand that we’re hoping to create.

Robert Klupacs [01:17:33] Fantastic. Thank you. Your turn, Andrew. As you mentioned in your talk, you’ve worked for organizations of very different sizes throughout your career. Can you tell us what the difference was between large companies and small startups? And you mentioned briefly embellish in terms of access to funding and culture. And also, what have you found common to both?

Dr Andrew Nash [01:18:03] Well so look.

Dr Andrew Nash [01:18:04] I mean comment both and and I guess that at a really fundamental level they’re the same you’ve just got two separate groups of investors that you have to convince that putting their money into your R&D is a good idea. So I guess it’s just a lot more cutthroat for the small companies. You know, the only thing they do is their R&D if they don’t get the money the company seeks to exist. But nevertheless, they’re investors, they’re bases that angel investors have to be convinced that they’re on the right pathway for us. You know, our shareholders are looking for return on their investment as well. So, you know, we constantly have to be able to justify the level that we spend on R&D in terms of a return to those investors. You know, the difference for us is that it might be a difference between nine, ten, 12% of revenue on R&D versus 15% of revenue on R&D. So R&D goes on, but it’s the level of the investment. So but but ultimately and at a fundamental level, you know, you’re trying to keep your investors happy and trying to help them understand that if you’re not innovating and you’re not moving forward, then ultimately you’re not going to be competitive.

Robert Klupacs [01:19:15] Fantastic. Thank you. Michelle the starting back with you again. From your experience in your current role at MIPS. What do you believe are the solutions to the challenges faced by organizations and inventors seeking to create products that will improve human health?

A/Prof Michelle McIntosh [01:19:38] I think that’s probably one of the biggest challenges is the the lack of appetite for risk in Australia and a fundamental culture of failure in Australia is not viewed as a learning experience. It’s like, oh, you’ve, you’ve failed at leading a major program or your technology failed. It might be nothing to do with your skills as a leader or a scientist, but you know, in the US, you know, you really you have, you haven’t done start ups and biotechs until you’ve failed about eight times and then maybe the ninth or 10th time. And so I think it’s a cultural thing around appetite for for risk and accepting that failure is part of the journey.

Robert Klupacs [01:20:33] Great. Thanks very much. Over to you, Megan. In your in your recent article, you made mention of the newly announced 1.5 billion medical manufacturing fund, and you mentioned that it was a fantastic opportunity to strengthen Australian in the biotech industry. What do you think should be some of the key funding principles of this fund to best support and grow the Australian industry?

Dr Megan O’Connor [01:20:58] Yeah, it is a very exciting opportunity that some that we have. First, I would like to see all industry participant participants be able to access the programs that come out of the fund. And that would include the pre-revenue companies. So as as we all are very much aware, the industry is mainly made up of SMEs. So 80% of the industry are SMEs and most of them, majority of them are pre-revenue. So typically that that in the past manufacturing focused programs have had a requirement that the companies need to be revenue generating and already have customers in that market. If that was the case, it would just shut out a lot of the industry to access that that great. Lots of a lot of funding there. At the same time, I would love to say it’s a it’s a significant fund able to make a significant impact. So I would love to see some big projects, some big ambitious projects that can make a difference, inspire us, put us on the you know, move the dial. And I think a success metric would be obviously to strengthen the industry. And that would one of the metrics there would be from growing able to grow small companies to medium companies and then the medium companies to large other large companies just like CSL, because with that growth, that’s where we’re going to get that skill development, both the breadth of skills and then the depths of skills that we need to be able to commercialize research effectively in Australia.

Robert Klupacs [01:22:45] Great. Thank you very much. Over to you again, George. So as you mentioned before and we mentioned earlier, you’ve been very successful in Australia, you’re now pushing into the Northern Hemisphere. You’ve recently announced an investment from Breakthrough Victoria to support you in that activity. What role do you see for government, for internationalizing Australian businesses, which is a journey that you’re on?

Dr George Kenley [01:23:08] A huge role and in multiple different kind of facets. So for us in our particular situation, so they’re basically a consumer. They are also a cheerleader for us in and they’re also fostering an ecosystem there in which we are one of many that are operating. So with us they are consumer, so we have a reimbursed service that we offer across Australia. So they are basically helping us to deliver that service to citizens of Australia with those with living with epilepsy. So that has allowed us to build our business here in Australia. We are in home soil whereby we can test what we’ve provided, really refine our commercialization strategy. But they’ve also then shifted into a cheerleading mode for us as well with the Breakthrough Victoria kind of funding. So our launch into the UK recently was represented and attended by the Victorian Governor and we’ve had great representation from the govt in regards to that and it’s really kind of lifted our standing in the UK kind of NHS sector because we’ve had to, we’ve had someone who’s really endorsed what we do and really endorse what we do here in Australia. We probably could have done that our, our own on our own, but it would have been far more difficult and it’s something that we’re really wanting to leverage off in regards to fostering an ecosystem that we operate. We’ve taken advantage of the R&D tax incentive, the R&D tax incentive loans. We’ve been part of BMT, H, MRF, which has really helped us kind of take calculated risks or not risk, but calculated steps by leveraging off those and allowing us to really extend our runway so that we can still continue to trade.